The roots of this concept are to be found in postcolonial theory developed on the basis of Edward Said’s work (1979 [1978]) and the Philosophy of Liberation, which emerged in Latin America from 1969 onwards. As Enrique Dussel (2020) points out, the decolonial theory as well as decolonising practices are in a process of constant evolution as they require a persistent critical exercise of the systems of power that operate at the institutional, systemic, discursive and epistemic levels. Liberation philosophy signified an awareness of the ‘Hellenocentrism’ of philosophy, which led to a critique of Eurocentrism and its consequent epistemic colonialism (Dussel, 2020). That is, the colonisation of minds and ideas through Western thought that is assumed to be universal, and which legitimises the racial and cultural superiority of Europe. Hellenocentrism constitutes the core of humanism and both are linked to the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, key moments in Europe’s colonial expansion. Epistemic colonialism and territorial colonialism are therefore sides of the same coin.

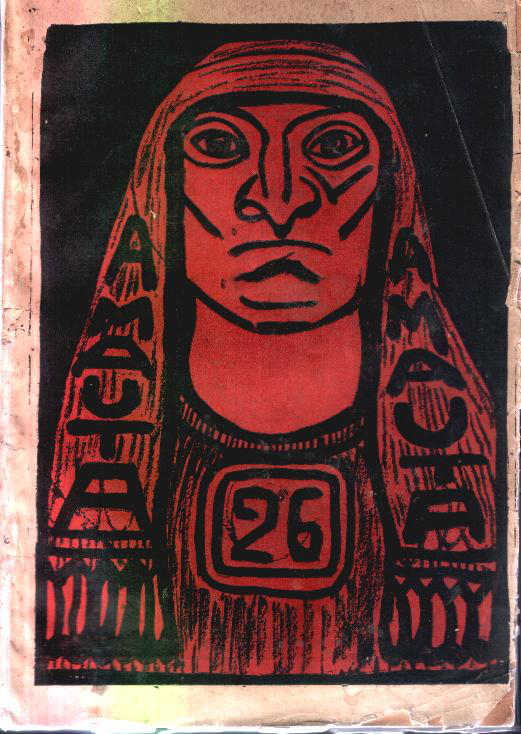

On the other hand, Robert J.C. Young explains that postcolonialism, which began in the 1990s, “is a term that represents critical perspectives of resistance to colonialism or colonial attitudes” (Young 2020, p. 3). This explains why postcolonial studies have responded to the decolonial thinking developed in Latin America. With this we can conclude that both, postcolonial studies and decolonial thought, have an important political dimension that makes explicit the need to decolonise; and whose focus of action and analysis is the Global South. This anti/de-colonial impulse is reflected in the discourses on Indianism and negritude developed in Latin America and the Caribbean. First of all, it is important to highlight the work of José Carlos Mariátegui and his avant-garde journal Amauta (fig. 1) – a Quechua and Aymara word that refers to the indigenous worldview of the thinker, creator and conductor of ideas. Secondly, Fausto Reinaga’s work represents the transition from Mariátegui’s Marxist indigenism to an indianism that vindicates “aumátic” thought (Oliva, 2014, p. 126).

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.es

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Cover_of_Amauta_-26.jpg

In the same way, Cecilia Vicuña’s khipus materialise and make absences and memories visible, connecting Andean culture with contemporaneity. Vicuña’s relationship with khipus had begun around 1966, wherefrom onwards these objects served as a guiding thread for her to develop a body of work that we could understand as Indianist, giving voice and discursive agency to the Andean cosmovision that inspires them. His Quipu Desaparecido (2018) (fig. 2) makes the absences of abysmal thought visible (De Souza Santos, 2014), but also that of thousands of people disappeared by military dictatorships in Latin America.

Furthermore, the discourse on negritude articulated by Aimé Césaire and Franz Fanon represents an emancipatory and vindicatory project of African culture and its diaspora. This can be seen reflected in the painting Tercer Mundo by the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam (fig.3), who in fact “understood his painting as ‘an act of decolonisation’” (Barreiro López, 2016, p. 36), and in which it is possible to see the disruptive force of surrealism and negritude.

These case studies highlight the decolonising potential of Indianism and negritude, disrupting the Manichean world of colonialism and the Cold War in order to put at the centre intermediate lines, intersections, confluences and fractures that generated the Third World: the geographical and conceptual space that gave the decolonial discourse enunciating agency, and that is today understood as the Global South.

Bibliography

Césaire, Aimé. (2006 [1950]), Discurso sobre el colonialismo, Ediciones Akal, Madrid, pp. 13-43.

Barreiro López, P. (2016), «Algarabía tropical en la vanguardia: Wifredo Lam, la izquierda cultural española y la Cuba revolucionaria», en Catherine David (dir.), Wifredo Lam, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, catálogo de exposición, pp. 35-41.

De Sousa Santos, B. (2014), «Más allá del pensamiento abismal: de las líneas globales a una ecología de saberes», en B. de Sousa Santos y M.P. Meneses (eds.), Epistemologías del Sur (Perspectivas), Ediciones Akal, Madrid.

Dussel, E. (2020), Siete ensayos de filosofía de la liberación. Hacia una fundamentación del giro decolonial, Editorial Trotta, Madrid [versión Kindle].

Fanon, Franz. (2007 [1961]), The Wretched of the Earth, Grove Press, Nueva York, (versión Kindle).

Gilroy, P. (1993), The Black Atlantic. Modernity and Double Consciousness, Verso, Londres.

Grosfoguel, R. (2006), «Del final del sistema-mundo capitalista hacia un nuevo sistema-histórico alternativo: la utopística de Immanuel Wallerstein», Nómadas, 25, pp. 44-52.

Mignolo, W. (2008), «La opción descolonial», Letral, 1, pp. 1-22.

Moraña, M. et.al. (eds.) (2008), Coloniality at Large. Latin America and the Postcolonial Debate, Duke, Durham.

Oliva, M. E. (2014), La negritud, el indianismo y sus intelectuales: Aimé Césaire y Fausto Reinaga, Editorial Universitaria, Santiago de Chile.

Quijano, A. (2000), «Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina», en Edgardo Lander (comp.), La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas, CLACSO, Buenos Aires.

Said, E. (1979 [1978]), Orientalism, Vintage Books, Nueva York.

Young, R.J.C. (2020), Postcolonialism. A very short introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford.