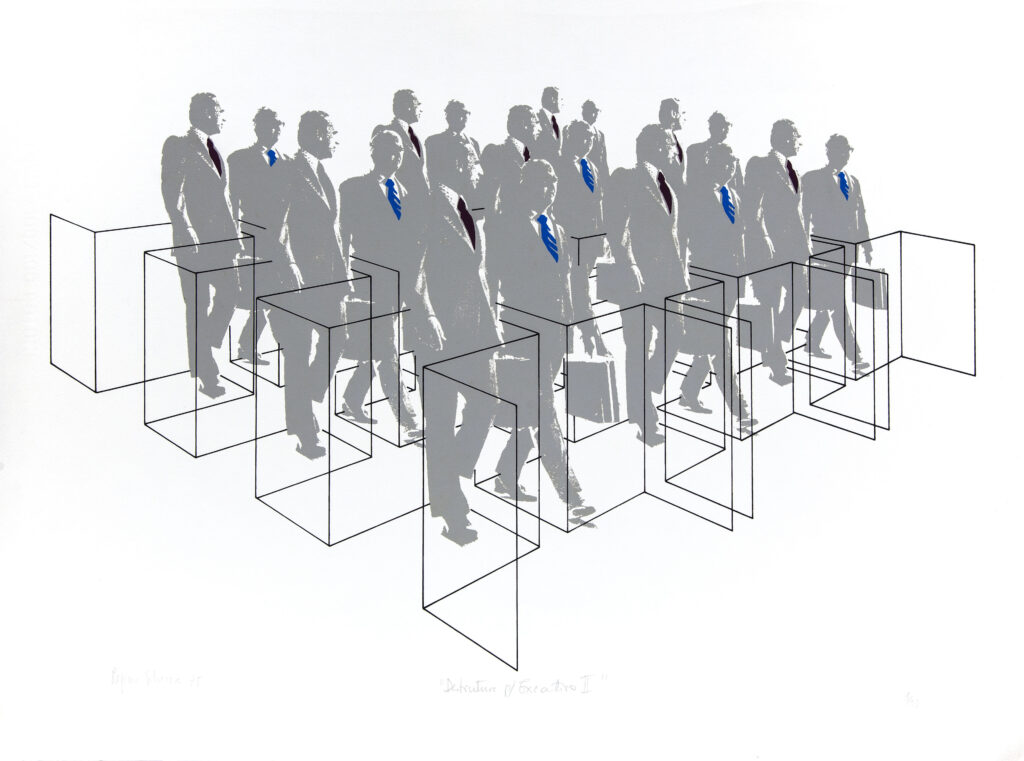

In the decades following the Second World War one can remark a growing presence of services, administration and information in productive structures. A post-industrial society is emerging, managed by bureaucrats relying on the technification of the processes of social organisation. Although rational management models claim to be apolitical, the sociology and the critical theory of the 1950s and 1960s already points towards the existence of an underlying ideology that, far from approaching democratic positions, employs the economic logics of neoliberal capitalism.

Technocracy has a political side, organised around the rational-scientific procedures of administration, and a technological side, which takes the applications of science and technology in the social production and reproduction into account. A good place to observe its effects is the art-technology relationship. If social thought oscillates between optimistic and pessimistic positions with respect to technocratic ideology, something similar happens in the arts. In the transition from the 1970s to the 1980s, art theory deals with this split field, reflecting on the updated use of technological tools – television, video and other new media used for the arts – and their uncritical and alienating use, which resulted in mere transmission of information (informativiso) and syntaxes emptied of its content, or in colonising cultural uses.

However, these assumptions of the mid-twentieth century were to be confirmed in the following decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, the development of the digital era extended information (IT) and communication technologies (ICT) in a world open to globalisation. Just as it was the case with the audio-visual technology of television and other mass media, with IT and ICT, rather than undoing centre-periphery hierarchies, they accentuate them under the aegis of a worldwide technocratic domination.

The advent of the Internet is accompanied by the control of migratory flows and cultural policies of inclusion-exclusion. The local and the global become confused, and multiculturalism emerges as a current of technocratic management applied to the field of identities. The most critical positions with respect to westernising modes of socio-morphogenesis remain on the margins, under the hegemony of neoliberal optimism.

Cyberculture first appears as an alternative space that facilitates the horizontal exchange of information and positions. Although the virtual sphere is soon recognised as a reproduction of external inequalities, areas such as cyborg thought, cyberfeminisms or the semiotic guerrillas of the net.art support the theoretical-practical overcoming of the long series of essentialist dichotomies operating under Western-centric reason.

Today, semio-capitalism rules every aspect of life, and dichotomous alternatives return: In the face of the anthropo-systemic entropy in an ecologically limited world, is active harnessing more useful or the opposition to technocratic reason? Even so, arts and culture no longer question the inside-outside of technocracy, but its inscriptions on bodies, minds and things.

Bibliography

Acha, J. (1981), Arte y sociedad: Latinoamérica. El producto artístico y su estructura, Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

Bell, D. (1973), El advenimiento de la sociedad post-industrial, Alianza, Madrid. Reeditado en 1991.

Berger, R. (1977), «Video and the Restructuring of Myth», en Douglas Davis y Allison Simmons, eds., The New Television: A Public/Private Art, The MIT Press, Cambridge, pp. 206-221.

«Bifo» Berardi, F. (2017), Fenomenología del fin. Sensibilidad y mutación conectiva, Caja Negra, Buenos Aires.

Gouldner, A.W. (1976), The Dialectic of Ideology and Technology. The Origins, Grammar, and Future of Ideology, The MacMillan Press, Londres.

Gubern, R. (1996), Del bisonte a la realidad virtual. La escena y el laberinto, Anagrama, Barcelona.

Haraway, D. (1984), «Manifiesto para cyborgs: ciencia, tecnología y feminismo socialista a finales del siglo xx», en Donna Haraway, Ciencia, cyborgs y mujeres. La reivindicación de la naturaleza. Cátedra, Madrid, pp. 251-311.

MacBride, S., ed. (1980), Un solo mundo, voces múltiples. Comunicación e información en nuestro tiempo, Fondo de Cultura Económica, México. Reeditado en 1993.

Marchán, S. (1972), Del arte objetual al arte de concepto, Akal, Madrid. Reeditado en 1994.

Marcuse, H. (1964), El hombre unidimensional. Ensayo sobre la ideología de la sociedad industrial avanzada, Seix Barral, Barcelona. Reeditado en 1971.

Meynaud, J. (1964), La tecnocracia. ¿Mito o realidad?, Tecnos, Madrid. Reeditado en 1968.

Minh-ha, T.T. (1989), Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Srnicek, N. (2017), Platform Capitalism, Polity Press, Cambridge y Malden.

Weibel, P.; Druckrey, T. (2001), eds., net_condition. Art and Global Media, MIT, Cambridge.

Youngblood, G. (1970), Expanded Cinema, P. Dutton & Co, Nueva York.