Undoing Absence to Reveal Violence

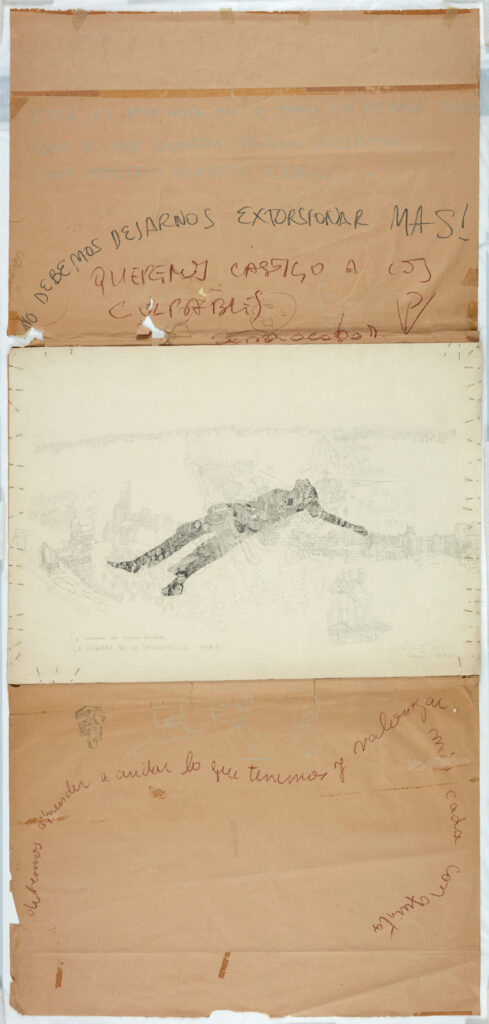

How can we think with and through deeply political artistic and visual practices that have been deployed to make absence present in contexts of political violence? By extension, how can we identify the role these practices play in the constitution, reconfiguration and transformation of political and social imaginaries that are in some way linked to the Cold War, its reorganisation of transnational forms of resistance and its legacy? The concept of corporeal evidence(s) draws attention to the centrality of the body in artistic and visual practices – practices developed by artists and collectives deeply involved in the social movements that contested the strategies of enforced disappearance in the wave of dictatorships that swept the Southern Cone of Latin America during the 1970s and 1980s – which created new visual languages to signal forms of bodily absence intended to make visible the unseen and the unspoken.

The concept emphasises the centrality of the body and its visual representation in artistic practices that have sought to undo absence, attempting to transform it into presence. On the one hand, it focuses our gaze on the probationary potential of the body (Maguire and Rao, 2018) and its capacity to traverse, inhabit, or even constitute multiple contexts and knowledges. It unravels “what a body can” (Expósito, 2009), that is, the representational, material and symbolic possibilities that the human form offers when it is activated to make visible violence and the power structures that support it.

Bodily evidence(s) also helps to trace the circulation of these practices beyond geopolitical boundaries, pointing to what Diana Taylor describes as a “repertoire” of performative actions in which images – family photographs, silhouettes, cropped snapshots – are activated to make visible the absence provoked by enforced disappearance. At the same time, it considers the movement of these practices through multiple temporalities, as well as demonstrating how the “forensic” image has been used in contemporary contexts to document and narrate the recovery of the bodies that the disappearance left behind and that were exhumed from mass graves. In this context, the concept helps to understand visual practices linked to the reappearance of the victims’ bodies as “counter-forensic” practices, where “the adoption of forensic techniques (are) a ‘political manoeuvre’, as a tactical operation in a collective struggle, a rebellious and resistant gallery for documenting the microphysics of barbarism” (Keenan 2014). That said, this concept also emphasises how counter-forensic images activate and operationalise the evidential mechanics, traditionally employed via state structures, to create new ‘bodies of evidence’, new corporeal evidence(s) that illuminate not only the mechanics of state violence, but also other horizons for narrating, when thinking and producing other knowledge and knowledges about the past.

This constellation of approaches – the image as a device that oscillates between the probative and the affective, between truth and memory; and the counter-forensic as an aesthetic that evidences but also narrates in order to undo the structures that allowed disappearance – brings us back to observe the creation of new languages used to make present what is not there from another point of view.

Bibliography

Blejmar, Jordana, Luis Ignacio García y Natalia Fortuny (2013), eds., Instantáneas de la memoria: fotografía y dictadura en Argentina y América Latina. Librería ediciones, Buenos Aires.

Camnitzer, Luis (1994), «Art and Politics: The Aesthetics of Resistance», NACLA Report on the Americas, 28, New York, pp. 38-45.

Carvajal, Fernanda y Jaime Vindel (2013), «Acción relámpago», en Perder la forma humana: una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, pp. 43-50.

Csordas, Thomas J. (2004), «Evidence of and for what», Anthropological Theory 4, London, pp. 473-80.

Douglas, Lee (2022), «Undoing Absence: Reflections on the Counter-Forensic Photo Essay», Writing with Light Magazine, 1, pp. 4-7.

Expósito, Marcelo (2009), No reconciliados (nadie sabe lo que un cuerpo puede), Hamaca, Barcelona.

Keenan, Thomas (2014), «Counter-forensics and Photography», Grey Room, 55 (Spring), pp. 58–77.

Maguire, Mark y Ursula Rao (2018), «Introduction: Bodies as Evidence» en Mark Maguire, Ursula Rao y Zils Zurawski, eds., Bodies as Evidence: Security, Knowledge, and Power, Duke University Press, Durham, pp. 1-23.

Richard, Nelly (2007), Márgenes e instituciones: arte en Chile desde 1973, Ediciones Metales Pesados, Santiago de Chile.

Rolnik, Suely (2008), «Furor de archivo», Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal, IX: 18-19, pp. 9-22.

Sekula, Allan (1986), «The Body and the Archive», October, 39, Winter, pp. 3-64.

Taylor, Diana (2003), The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, Duke University Press, Durham.

Varas, Paulina y Javiera Manzi (2013), «Documentográfica», en Perder la forma humana: una imagen sísmica de los años ochenta en América Latina, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, pp. 99-102.

Weiss, Peter (2016 [1975]), The Aesthetics of Resistance, volúmenes 1 & 2, Neugroschel, Joachim, transl., Duke University Press, Durham.

Weizman, Eyal (2014), «Introduction: Forensis”, en Forensis: Forensic Architecture, Berlin, Sternberg Press, pp. 9-32.

Dziuban, Zuzanna (2017), «Introduction: Forensics in the Expanded Field», en Zuzanna Dzuiban, ed., Mapping the “Forensic Turn:” Engagements with Materialities of Mass Death in Holocaust Studies and Beyond, Vienna, New Academic Press, pp. 7-35.