Labour and the construction of subjectivity in contemporary neoliberal capitalism

Traditionally, the history of contemporary labour is delineated by a timeline that begins with the first industrial revolution (with the coal powered steam engine and culminating in the Fordist production system), continues with the second industrial revolution driven by oil after the Second World War – and which would feed so-called post-Fordism; this gave then way to the third revolution determined by digitalisation and the accelerated processes of globalisation that emerged in the 80s of the last century and would eventually culminate in what we currently call the fourth industrial revolution that bases on the development of Artificial Intelligence and the robotisation of production processes.

But this continuous timeline, which fits very much the modern Western taste and its idea of indefinite progress is nevertheless much more complex and fragmented and involves brutal processes of subjection: neither the industrialisation and its subsequent consequences were the same on all continents, nor is the supposed progressive “immaterialisation” of capitalism true. Behind today’s informational capitalism there is a huge amount of “material” labour hidden that is mainly performed by racialised people and highly feminised; not only invisible “reproductive” labour – poorly paid or unpaid (as well as socially devalued) – , but also huge amounts of labour in polluting or heavy industries, which has been delocalised outside the Western-centric space (China, India, Indonesia… the big factories of today’s world).

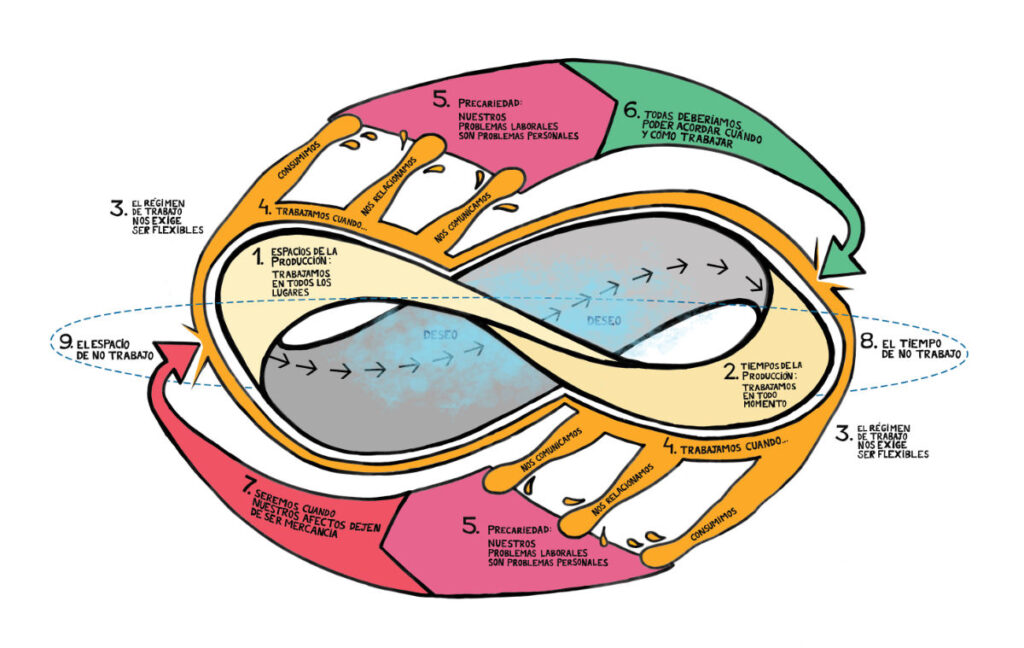

The last decades of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century coincide with the alignment of neoliberalism with capitalism and the technological revolution brought about by the digitalisation, robotisation and financialising of the economy (the new niche of capital, whose accumulation was slowed down by the very frontiers of productive capacity and the limits of the planet). (…) The most visible work becomes immaterial, the generation and dissemination of information that does not belong to its workers, dispossessed of the knowledge produced and co-opted by neoliberal semiocapitalism (Francesco “Bifo” Birardi): platform capitalism hides exploitation and hyper-flexibility under the lightness of the mobile telephone-office; the “false self-employed” become widespread; the university becomes a race against time for the quantification of a non-emancipatory knowledge at the service of power; the data provided by everyone for free on social networks feed the vectorial power of large companies (Google, Amazon, Facebook…) possessing a huge amount of completely asymmetrical power relation.

Outside the factory, the contemporary metropolis becomes a place of production, and our lives are spent without a distinction between time for living and work time because all the fissures in our lives have been captured and occupied by capital and are controlled by profitability. Work is not only a way of “earning a living” by losing it, but it becomes the fundamental strategy of disciplining our bodies and subjectivities.

Bibliography

Barrett, J. (2011), Museums and the Public Sphere, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester.

Bishop, C. (2018), «Black Box, White Cube, Gray Zone: Dance Exhibitions and Audience Attention», The Drama Review, 62 (2), pp.22-42.

Calhoun, C. (ed.) (1992), Habermas and the Public Sphere, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma.

Carrier, D. (1986), «Art and Its Spectators», The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 45 (1), pp. 5-17.

Crary, J. (1990), Techniques of the Observer. On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma.

Hoelscher, S. (ed.) (2013). Reading Magnum: a visual archive of the modern world, University of Texas Press, Austin, p. 92.

Klaus, E. and O’Connor, B. (2000), «Pleasure and meaningful discourse: An overview of research issues», International Journal of cultural studies, 3 (3), pp. 369-387.

Leahy, H.R. (2012), Museum Bodies. The Politics and Practices of Visiting and Viewing, Routledge, London and New York.

Martin Prada, J. (2018), El ver y las imágenes en el tiempo de Internet, AKAL, Madrid.

Sobchack, V. (2004), Carnal thoughts. Embodiment and the moving image culture, California University Press, Berkeley.

Reyero, C. (2008), Observadores. Estudiosos, aficionados y turistas dentro del cuadro, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona.

Wesseling, J. (2017), The Perfect Spectator. The Experience of Art Work and Reception Aesthetics, Valiz, Amsterdam.

Wilder, K. (2020), Beholding. Situated Art and the Aesthetics of Reception, Bloomsbury, London.