1. Introduction to the case study

“Bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales”[1], the title of Ivo Mesquita’s article, as well as its incipit, an apparently infinite list of biennials, could not be more illustrative of the proliferation of these mega-exhibitions at a global level.

The complexity of the study of the biennial phenomenon lies not only in the large number of these artistic events (today more than two hundred) but in the specificity of each one. In fact, a biennial has local, regional/continental and global aspirations. Its founding motives are interrelated with the geopolitical context, as well as with the historical moment and the sources of funding. Furthermore, one cannot speak of Western and non-Western biennials only from a geographical point of view, since biennials in the South may have both Western and counter-hegemonic objectives, or may be financed by the North. Moreover, a biennial is not a static entity but one that is continuously evolving, therefore its approach, format or funding is subject to repeated changes and revisions.

Historically, two waves of biennials have been identified; the first between 1895 and 1984, at which time they were apparently few in number (Venice, 1895, Carnegie, 1896, São Paulo, 1951, Documenta, 1955 and Sydney, 1973) and the second after the first edition of the Bienal de La Habana (1984), from which time the biennials began to proliferate unchecked at the global level[2]. However, recent research has begun to rescue the biennials of the South (Hispanoamericana, 1951, Alexandria, 1955, Ljubljana, 1955, Medellín, 1968, New Delhi, 1968, San Juan, 1970), redefining the temporal arc of the second wave between the 1950s and 1980s[3]. Consequently, the proliferation of the biennial format took place starting in the 1950s and the second wave actually corresponds to a third.

The present study seeks to continue rescuing the stories of the biennials of the South, analyzing the biennialistic reality in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1951 and 1986. This time frame includes the period between the opening of the Bienal de São Paulo and the second edition of the Bienal de La Habana[4]. It was decided to start the study in 1951, with São Paulo being the first biennial in the region, and to finish it in 1986, because in its third edition (1989) Havana inaugurated a new exhibition model which marked a turning point in its history and in that of the biennials.

2. Methodology and visualization

The study seeks to map the biennials in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1951 and 1986, defining their characteristics and specificities and offering a first approach to this biennial environment. The research was articulated in 5 phases:

- a search for the biennials and collection of material

- Inserting the information into the MoDe(s) database

- Exporting the data and its preliminary analysis

- Definitive analysis and choice of visualization methods

- Visualization of the data and comparison of its visual efficiency and informative validity

The research and recompilation of the material was carried out in different institutions such as the study and documentation centre of the MACBA (Barcelona), the library and documentation centre of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid), the AECID library (Madrid) and the archive of the Centro Wifredo Lam (Havana). The online archives of the International Center for the Arts of the Americas (ICAA – Houston), the Museo de Antioquia (Medellín), the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP – San Juan) and the Biblioteca Nacional de Chile (Santiago) were also consulted. Sources used were mainly the catalogues of the biennials, articles in newspapers and journals, and academic essays.

The information gathered was intended to clarify the nature of these biennials (regional or international, competitive or not), the sources of funding (public or private) and the actors involved (the technical commission or the members of the jury).

The information was then entered into the MoDe(s) relational database. The database makes it possible to cross-check the data related to the biennials and to review possible intersections with data from other cultural events and other case studies of the Decentralized Modernities project.

After exporting the data and reviewing and filtering it, the analysis and selection of the forms of visualization was carried out, identifying the node diagram and the maps as the most suitable for the case study.

The information was then entered into the MoDe(s) relational database. The database makes it possible to cross-check the data related to the biennials and to review possible intersections with data from other cultural events and other case studies of the Decentralized Modernities project.

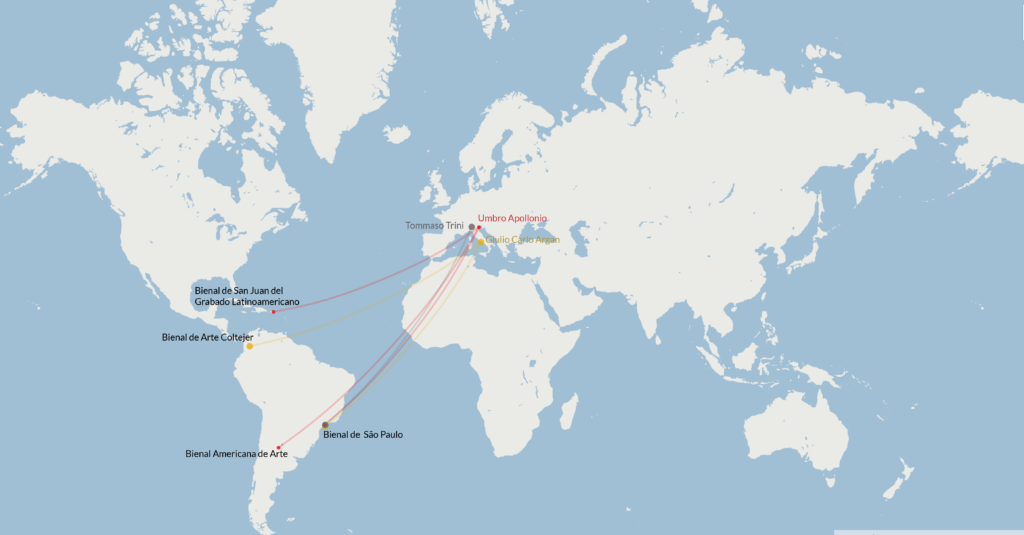

The maps provide a geospatial visualization of the biennials in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as the transnational networks that were established. To facilitate their reading, a color code has been used to identify a biennial and compare it with others.

3. Results obtained

3.1 Biennials: list and characteristics

The biennialistic reality in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1951 and 1986 was mainly made up of regional biennials with international aspirations, which adopted a competitive format, were financed by private funding and were of short duration[5].

If during the first decade of this analysis Brazil stands out as an international artistic epicenter, starting in the 1960s other countries such as Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Puerto Rico inaugurated their own biennials.

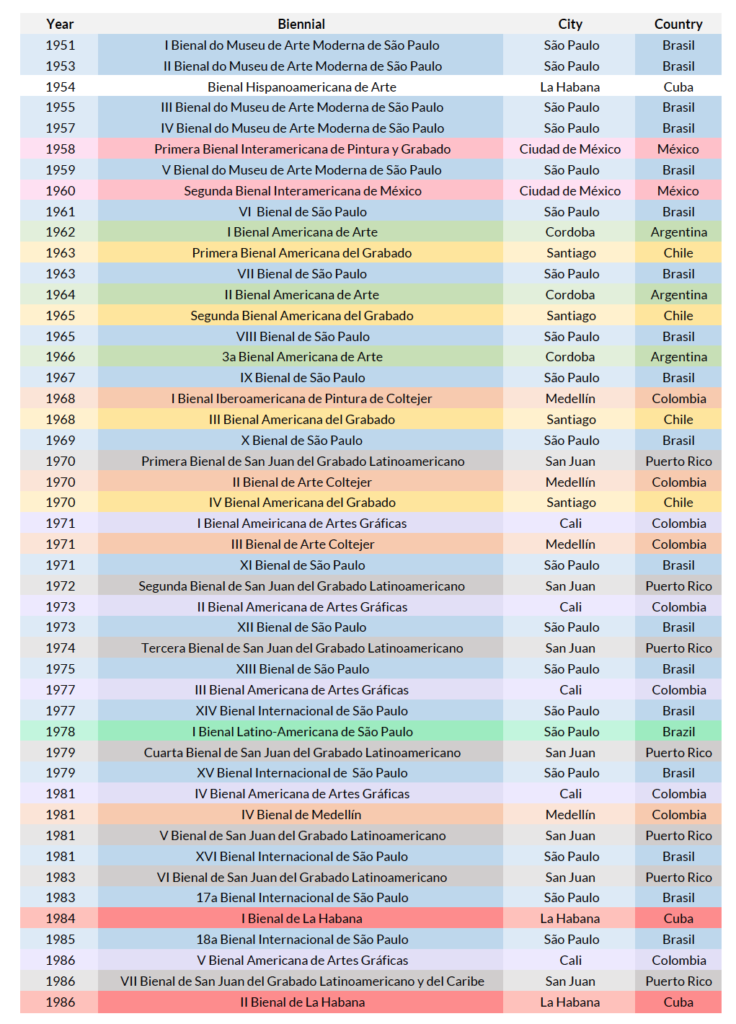

Most of these biennials were regional, that is, they were mainly aimed at countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. As shown in the list (fig. 1), their names contain adjectives such as American, inter-American, Ibero-American or Latin American.

With the exception of the biennials of São Paulo, San Juan and Havana, which are still active today, these events were of short duration (Bienal Interamericana de México, 1958 – 1960; Bienal Americana de Arte, 1962-1966; Bienal Americana del Grabado 1963-1965; Bienal Americana de Artes Gráficas, 1971-1986; Bienal de Arte Coltejer, 1968-1971)[6]. The end of these biennials is due to the scarcity of economic resources or the end of private support. Examples are the Bienal de Artes Gráficas, sponsored by Cartón de Colombia S.A., the Bienal Americana de Arte, sponsored by Kaiser Industry or the Bienal Arte Coltejer sponsored by Fábrica Textil Coltejer. In the latter case, an attempt was made to reactivate the artistic event in 1981 through the sponsorship of Medellín Cultura, this time calling it the Bienal de Medellín[7].

3.2 Inter-institutional and inter-biennial networks

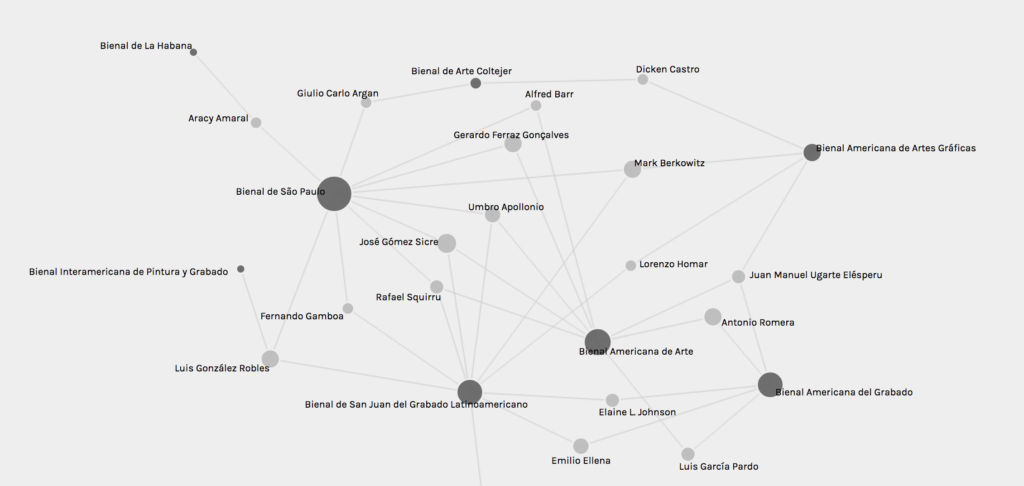

All of these biennials adopted the format of the Biennale di Venezia, i.e. an organizing committee, national entries and a competitive nature, based on the awarding of prizes after evaluation by a jury. An analysis of these biennials shows, on the one hand, that there were marked inter-institutional relations between the biennials and, on the other hand, that transnational networks were established with European or North American institutions. As the node diagram illustrates, some agents were involved in more than one biennial. Examples of these are the figures of Emilio Ellena, Elaine L. Johnson, Umbro Apollonio or José Gómez Sicre.

The figures of Emilio Ellena and Elaine L. Johnson allow us to highlight the existence of networks within the three biennials of engraving and the collaboration with the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA)[8]. In fact, Ellena was one of the organizers of the IV Bienal Americana del Grabado de Santiago (1970), a member of the commission of the Chilean submission to the First Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1970), part of the jury of the second edition (1972) and advisor on the Chilean participation in to the III Bienal Americana de Artes Gráficas de Cali (1977)[9]. On the other hand, Elaine L. Johnson, director of the Department of Drawing and Engraving of MoMA[10], was part of the jury in the III and IV Bienal Americana del Grabado (1968 and 1970) and in the First Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1970), event sponsored by the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP), with the support of the Museo de Arte de Ponce and MoMA[11].

Another member of the jury of the First Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1970) was Umbro Apollonio, an art historian linked to the Biennale di Venezia from 1953 to 1970. His figure also makes it possible to delineate the existence of contact between biennials thanks to the close links with the Bienal de São Paulo (between 1955 and 1973) and his participation as a member of the jury at the Second Bienal Americana de Arte de Córdoba (1964). The figure of Umbro Apollonio and the relations between São Paulo and Venice explain the interest that the Brazilian biennial had in establishing a dialogue with the hegemonic centers in Europe and the United States. This is also reflected in the collaboration with the Visual Arts Section of the Organization of American States (OAS) led by José Gómez Sicre[12]. The Cuban critic and curator was an advisor to the Cuban delegation in the first three editions (1951, 9153 and 1955) of the Bienal de São Paulo and curated a space dedicated to the OAS from the third to the ninth edition (1955 – 1967). Furthermore, his participation in the jury of several artistic events, such as the I and II Bienal Americana de Arte de Córdoba (1962 and 1964), the V Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1981) and several editions of the Bienal de São Paulo (1959, 1963 and 1965) confirms the multidirectional contacts between biennials.

3.3. North-South Axis / South-South Axis

The analysis of the jurors of these biennials allows us to emphasize the different focus of these events. As has been pointed out, almost all of these biennials were regional, that is, they sought to establish a dialogue and artistic exchange with a defined geographical area and not to be a stage for “international/universal” artistic production, as is the case with Venice or São Paulo. The biennials in question were intended to be representative of artistic production in Latin America and the Caribbean, including in some cases the participation of the United States[13] or invited countries[14].

One exception is Havana, whose purpose was to provide a platform for the study and exhibition of Third World artistic production. This objective was achieved in its second edition (1986), because the first has been limited to Latin America and the Caribbean.

Despite the fact that all these biennials promote South-South artistic exchange, an analysis of the jurors reveals how there is a different criterion when it comes to selecting the members of the jury.

The comparison between the juries of the 3ª Bienal Americana de Arte, II Bienal de Arte Coltejer and the II Bienal de La Habana underscores Cuba’s interest not only in being a Southern exhibition venue but also in evaluating artistic production according to Southern criteria rather than the canons, hierarchy of values and stylistic norms of the hegemonic centres in the Northern hemisphere.

The conspicuous participation of agents from the North in the biennials of Cordoba and Medellin reflects, beyond interest in establishing a dialogue with the hegemonic centers, how the center-periphery scheme had become more flexible but remained untouched.

This is also evident in the participation of different personalities (Giulio Carlo Argan, Umbro Apollonio and Tommaso Trini) linked to the Biennale di Venezia as members of the jury or curators in various biennials in the South. Giulio Carlo Argan was a member of the commission of experts in several editions of the Biennale di Venezia (1954, 1956, 1960 and 1970) and was part of the international jury in 1960. Argan curated, together with Lawrence Alloway and Vicente Aguilera Cerni[15], the II Bienal de Arte Coltejer (1970) and was part of the jury of the VII Bienal de São Paulo (1963).Umbro Apollonio was curator of the Archivo Storico d’Arte Contemporanea (1950-1970) of the Biennale di Venezia, co-secretary of several editions (1958, 1966 and 1968) and director of the 35th edition, where he curated the exhibition Proposte per un’esposizione sperimentale (1970). In the biennials under examination, Apollonio was part of the jury at the II Bienal Americana de Arte (1966), at the First Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1970) and at the III and XII Bienal de São Paulo (1955 and 1973).

Finally, Tommaso Trini, who was part of the commission of experts on Ambiente, partecipazione, strutture culturali (1976) and was curator of the Aperto section (1982) at the Biennale di Venezia, was a member of the jury at the 14th Bienal de São Paulo (1977).

4. Final considerations

Bienal (do Museu de Arte Moderna/Internacional) de São Paulo, Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte, Bienal Interamericana (de Pintura y Grabado) de México, Bienal Americana de Arte, Bienal Americana del Grabado, Bienal (Iberoamericana de Pintura) de Arte Coltejer (de Medellín), Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (y del Caribe), Bienal Americana de Artes Gráficas, Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo and Bienal de La Habana: between 1951 and 1986 there were 10 biennials in Latin America and the Caribbean for a total of 46 editions.

This study has made it possible to begin to map out this biennialistic reality, identifying specifics such as the regionalist nature, the competitive format or the short duration, linked to private financing. It has also led to the emergence of inter-institutional and inter-biennial networks, where in some cases the North-South axis is maintained and reinforced and in others a South-South axis is established. Furthermore, it has highlighted the role of reference that the Biennale di Venezia has maintained overseas, through the participation of intellectuals linked to it, both in the international juries and in the curatorship of the biennials. However, despite having begun to delineate the existence of networks, this research constitutes only a first and partial approximation to the complex, multidirectional and transnational biennial reality of Latin America and the Caribbean.

In fact, considering the biennials as zones of contact, the scene of artistic and curatorial circulations, of international meetings and of hybridization or transformation of ideas, it is worth asking what the cultural transfers of these circulations have been, not being limited only to the agents involved in the curatorship or the jury, but extending the questioning to the artists who participated in these biennials: What artistic networks were generated in and from these biennials? Is there a differentiating element in the artistic and curatorial networks in the engraving biennials with respect to the others? What were the consequences of a South-South dialogue tinged with international aspirations? What impact did the participation of agents from the North have in the biennials of the South? What was the result of this collaboration in the biennials of the North?

[1] Mesquita Ivo, “Bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales”, Revista de Occidente, no. 238, 2001, pp. 31-36.

[2] The proliferation of biennials accelerated from the mid-1980s, with a significant increase throughout the 1990s. See graph in Kolb, Ronald; Patel, Shwetal A., “Survey reviwe and consideration”, OnCurating, no. 39, 2018, p. 16.

[3] Garden, Anthony; Green, Charles, “1979: Cultural Translation, Cultural Exclusion, and the Second Wave” in Biennials, Triennials and documenta:the exhibitions that created contemporary art, Hoboken, JohnWiley & Sons Inc., 2016, pp. 49- 79.

[4] During the period in question, the Bienal de São Paulo assumed three designations: Bienal do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo (1951-1959), Bienal de São Paulo (1961-1975) and Bienal Internacional de São Paulo (1977 -1985). For easier reading, only the name Bienal de São Paulo will be used throughout this study.

[5] With the exception of I Bienal Latino-Americana de São Paulo (1978).

[6] In 2004 the Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano (1970-2001) became the Trienal Poli/Gráfica de San Juan.

[7] Ramírez González, Imelda, Debates críticos en los umbrales del arte contemporáneo. El arte de los años setenta y la fundación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Medellín, Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2010, p. 153. Medellín Cultura was an entity constituted by businessmen that also received public funding.

[8] Basilio, Miriam, “Recuperando a Elaine L. Johnson, comisaria entre campos enfrentados en The Museum of Modern Art durante la Guerra Fría”, in Barreiro López, Paula (ed.), Atlántico frío: historias transnacionales del arte y la política en los tiempos del telón de acero, Madrid, Brumaria, 2019, pp. 293-317.

[9] Castellanos Olmedo, Adriana, “Cali, ciudad de la gráfica: las Bienales Americanas de Artes Gráficas del Museo La Tertulia y Cartón de Colombia (1970-1976)”, Caiana. Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores del Arte, no. 8, 2016, pp. 17-30.

[10] Ellena, Emilio, Sobre las Bienales Americanas del Grabado. Chile, 1963 – 1970, Santiago de Chile, Centro Cultural de España, 2008, pp. 31-32. The contact between the Bienal Americana del Grabado and MoMA took place in its second edition when the North American institution sent a significant representation of graphic art. The contact happened thanks to the mediation of Nemesio Antúnez (promoter of the biennials together with Thiago de Mello) who was covering the position of cultural attaché at the Chilean embassy in New York.

[11] Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe, San Juan, Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2015, p. 4.

[12] Armato, Alessandro: “Una trama escondida: la OEA y las participaciones latinoamericanas en las primeras cinco Bienales de São Paulo”, Caiana. Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA), no. 6, 2015, pp. 33-43.

[13] One example is the Bienal America del Grabado , which extended its call to the entire American continent, or the 3a Bienal Americana de Arte, which, after two editions dedicated exclusively to Latin America and the Caribbean, included United States artists.

[14] Spain was the guest country at the I Bienal Iberoamericana de Pintura de Coltejer (1968) and at the II Bienal de Arte Coltejer (1970).

[15] It should be noted that Vicente Auilera Cerni was awarded the International Prize for Art Critics at the 29th Biennale di Venezia (1958) and in 1960 he participated in the committee for this prize, together with Giulio Carlo Argan. See Barreiro López, Paula, Avant-Garde Art and Criticism in Francoist Spain, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2016, p. 135.

Bibliography

“La Bienal de Córdoba: movimiento para el diálogo americano”, Gacetika, vol. 7, no. 71, 1964, pp. 3-6.

1a Bienal Americana del Grabado, Santiago de Chile, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, 1963.

3a Bienal Americana de Arte, Córdoba, [s.n.], 1965.

Armato, Alessandro: “Una trama escondida: la OEA y las participaciones latinoamericanas en las primeras cinco Bienales de Sao Paulo”, Caiana. Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores de Arte (CAIA), no. 6, 2015, pp. 33-43.

Barreiro López, Paula, Avant-Garde Art and Criticism in Francoist Spain, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2016.

Basilio, Miriam, “Recuperando a Elaine L. Johnson, comisaria entre campos enfrentados en The Museum of Modern Art durante la Guerra Fría,” en Barreiro López, Paula (ed.), Atlántico frío: historias transnacionales del arte y la política en los tiempos del telón de acero, Madrid, Brumaria, 2019, pp. 293-317.

Bienal 50 años. 1951-2001, São Paulo, Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2010.

Bienal de San Juan del Grabado Latinoamericano y del Caribe, San Juan, Museo de Historia, Antropología y Arte Universidad de Puerto Rico, 2015

Castellanos Olmedo, Adriana, “Cali, ciudad de la gráfica: las Bienales Americanas de Artes Gráficas del Museo La Tertulia y Cartón de Colombia (1970-1976)”, Caiana. Revista de Historia del Arte y Cultura Visual del Centro Argentino de Investigadores del Arte, no. 8, 2016, pp. 17-30.

Ellena, Emilio, Sobre las Bienales Americanas del Grabado. Chile, 1963 – 1970, Santiago de Chile, Centro Cultural de España, 2008

Garden, Anthony; Green, Charles, “1979: Cultural Translation, Cultural Exclusion, and the Second Wave” en Biennials, Triennials and documenta:the exhibitions that created contemporary art, Hoboken, JohnWiley & Sons Inc., 2016, 2016, pp. 49- 79.

Halaby, Alexa, “Bienales de Arte Coltejer 1968, 70 y 72: seis años de revolución cultural en Medellín, Colombia”. En línea: https://www.guggenheim.org/es-us/blogs/map/bienales-de-arte-coltejer-1968-70-y-72-seis-anos-de-revolucion-cultural-en-medellin-colombia (Consulta: 05/05/2020)

I Bienal de La Habana 84, Havana, Dirección de Artes Plásticas, 1984.

I Bienal Iberoamericana de Pintura Coltejer, Medellín, [s.n.], 1968.

II Bienal de Arte Coltejer, Medellín, Colonia, 1970.

III Bienal Americana del Grabado, Santiago de Chile, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, 1968.

IV Bienal Americana del Grabado, Santiago de Chile, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, 1970.

Kolb, Ronald; Patel, Shwetal A., “Survey reviwe and consideration”, OnCurating, no. 39, 2018, pp. 15-34.

Mesquita Ivo, “Bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales, bienales”, Revista de Occidente, no. 238, 2001, pp. 31-36.

Ramírez González, Imelda, Debates críticos en los umbrales del arte contemporáneo. El arte de los años setenta y la fundación del Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, Medellín, Fondo Editorial Universidad EAFIT, 2010.

Rocca, María Cristina; Panzetta, Ricardo, “Bienales de Córdoba: arte, ciudad e ideologías”, Estudios, no. 10, 1998, pp. 93-108.

Segunda Bienal Americana del Grabado, Santiago de Chile, Editorial Universitaria, 1965.

Segunda Bienal de La Habana 86, La Habana, Editorial de Cultura y Ciencia, 1986.

Tercera Bienal de Arte Coltejer, Medellín, Colonia, 1972.