What place do technology and digital means occupy for MoDe(s)? As numerous theorists of digital art history already stressed, digital art history is not an isolated branch of art history. Agreeing with this idea, we consider that digital art history can contribute to a broader reflection on the articulation of cultural and political practices during the Cold War, just as other methods and forms of inquiry do: not as a separated field of historiographical practice.

Focusing more specifically on the question of mapping, the analysis of geographic data through the lens of different theoretical frameworks and critical methodologies – such as those introduced by cultural and postcolonial studies, decolonial thinking, or feminism – allows us to plot complex information concerning artistic tendencies in the context of the Cold War, keeping in mind their social and ideological backgrounds.

We have implemented the visualization of research data (extracted from MoDe(s) Database, see here) through Geographic Information Systems. Filtered contents from the Database are mapped thanks to programs like QGIS, which makes possible to display cultural facts and analyse them from a broad range of perspectives.

First case: Mail Art

We worked with a first case of study to test the functioning of the Database and its connectedness with GIS programs: Mail Art exhibitions over the 1970s decade.

Mail Art is an example of artistic practice that emerged and developed within the temporal framework of our project, and was extremely mobile and in constant circulation.

It presents a number of characteristics that make it a particularly fascinating case to study from a spatial perspective:

- It relied on transnational networks, diffused through national and international postal services.

- It was inclusive: everyone could participate (no jury, no return).

- As such, it propagated worldwide, without distinction between centers and periphery (a “democratic” artistic language).

- It allowed artists from distant countries to get in contact and exchange, sometimes in the context of dictatorships (LA, EE).

- It spread solidarity, internationalism, friendship: immaterial aspects that are also at the centre of MoDe(s)’ interests.

- It put the emphasis on communication processes rather than material production.

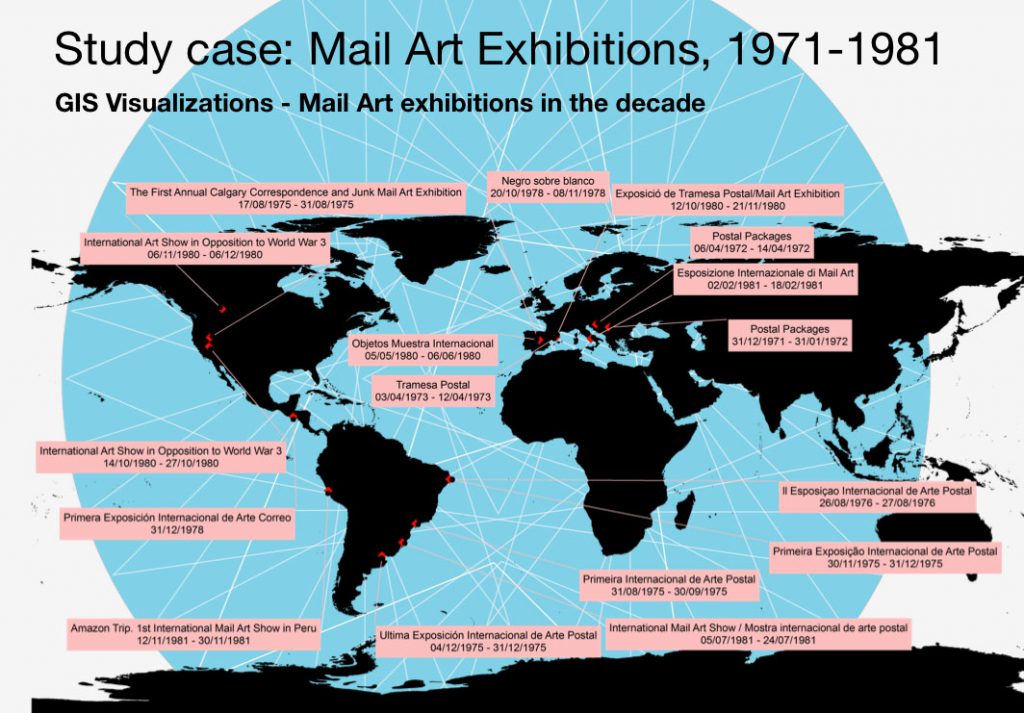

Facing such a moving and ephemeral practice, the exhibitions gathering Mail Art works represented some focal points, through which these practices could be – at least temporarily – fixed with geographical coordinates.

Mapping Mail Art

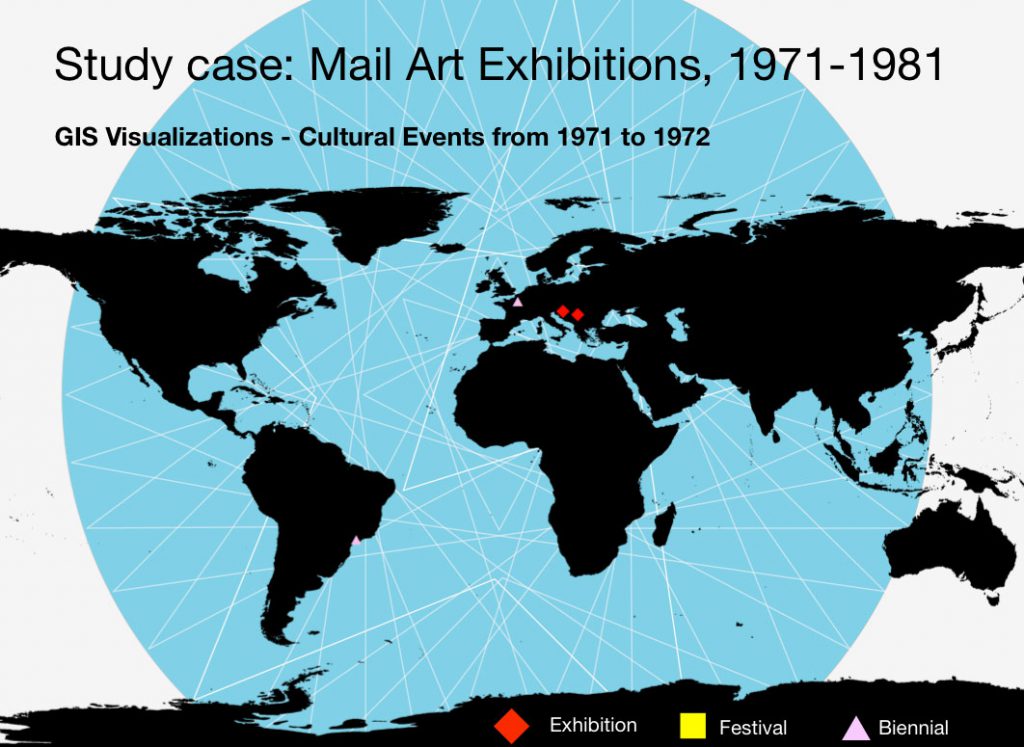

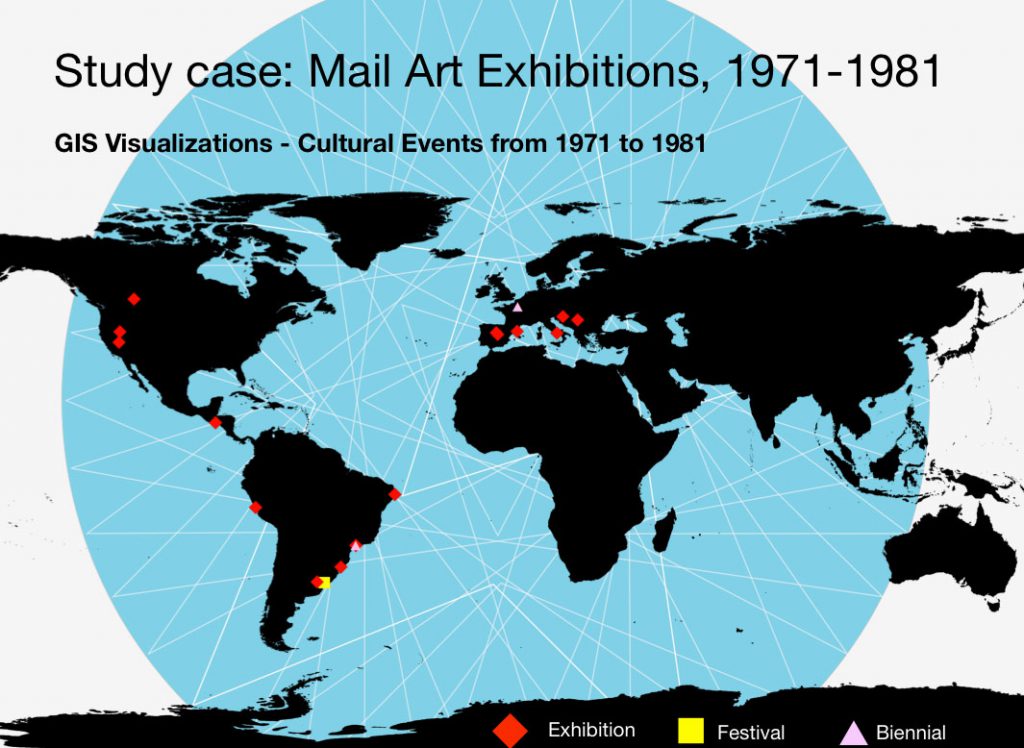

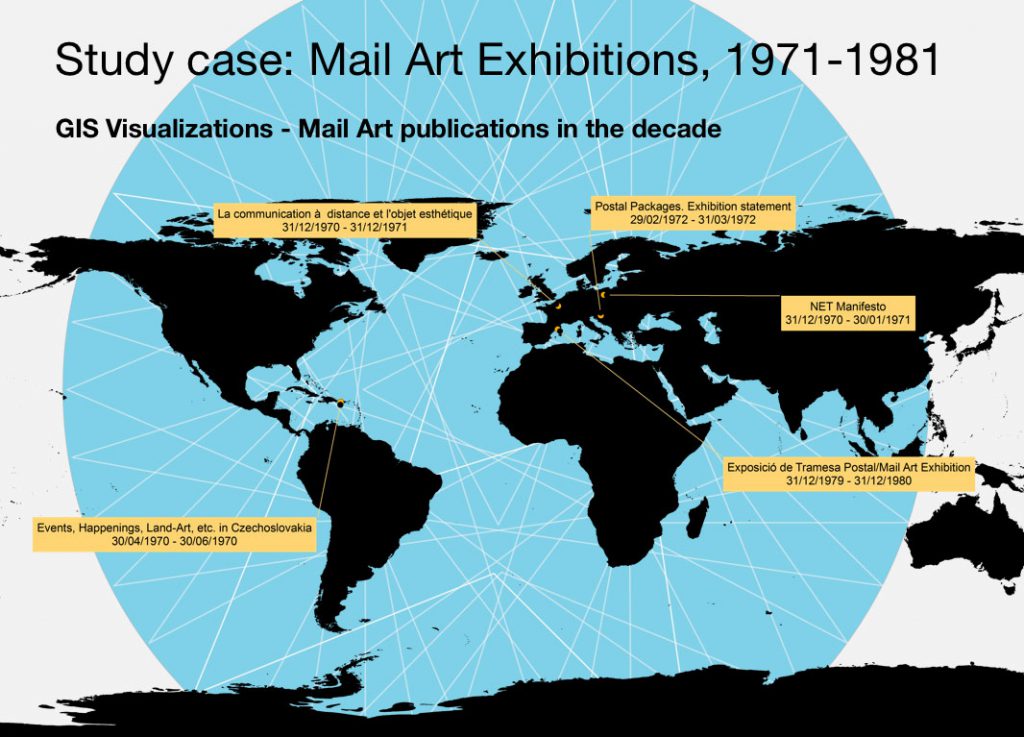

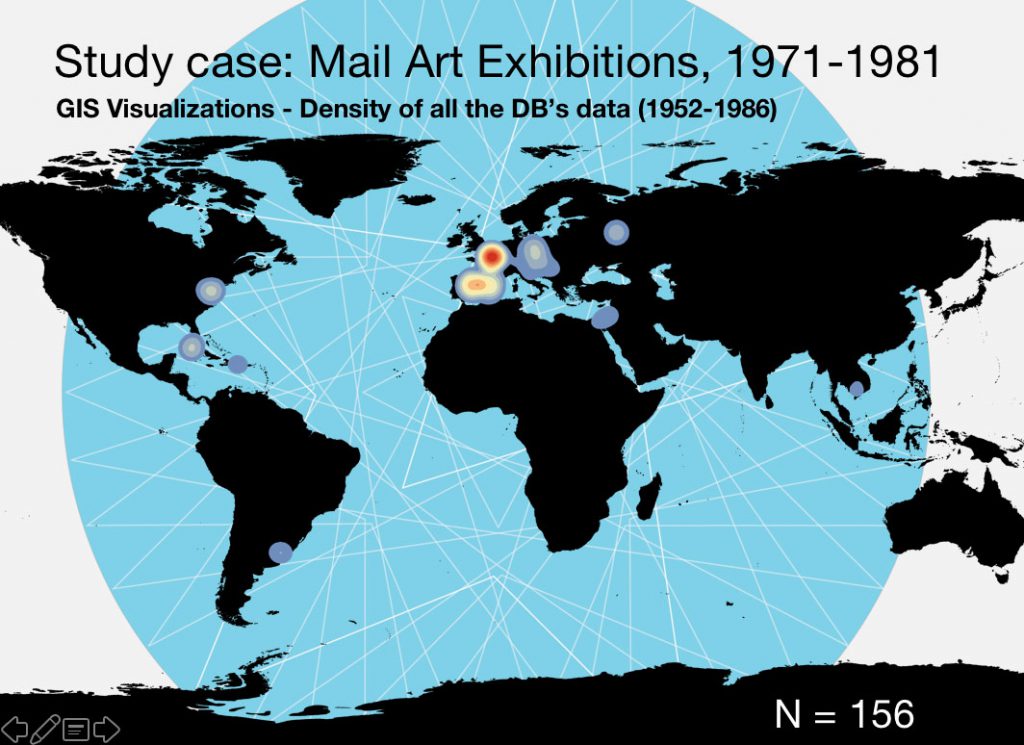

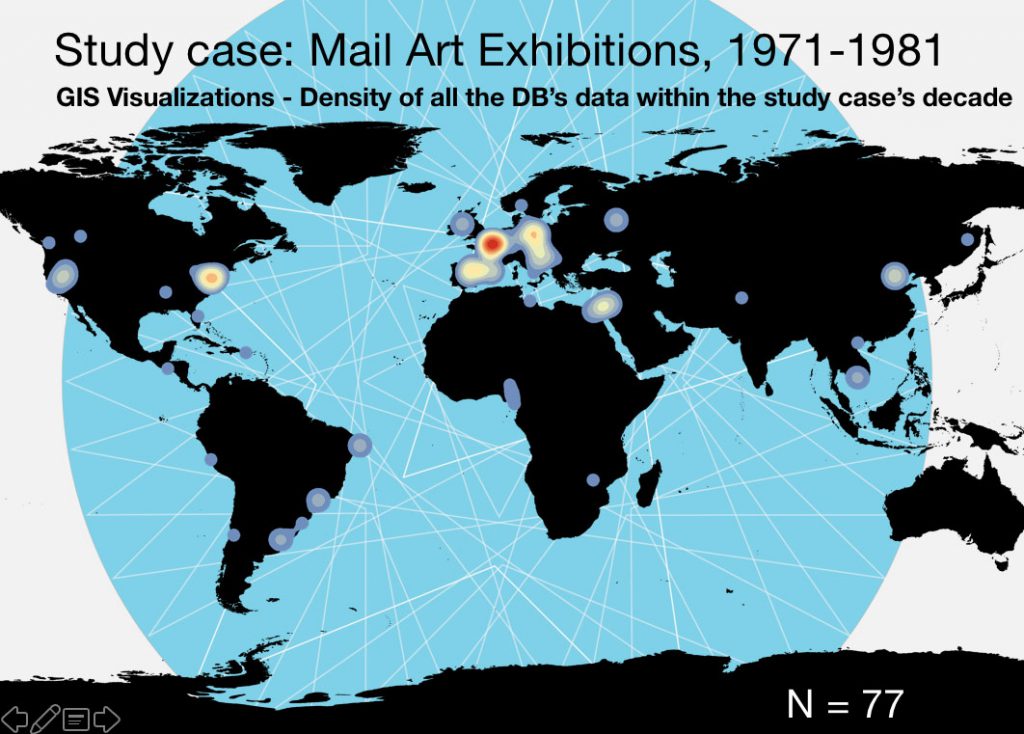

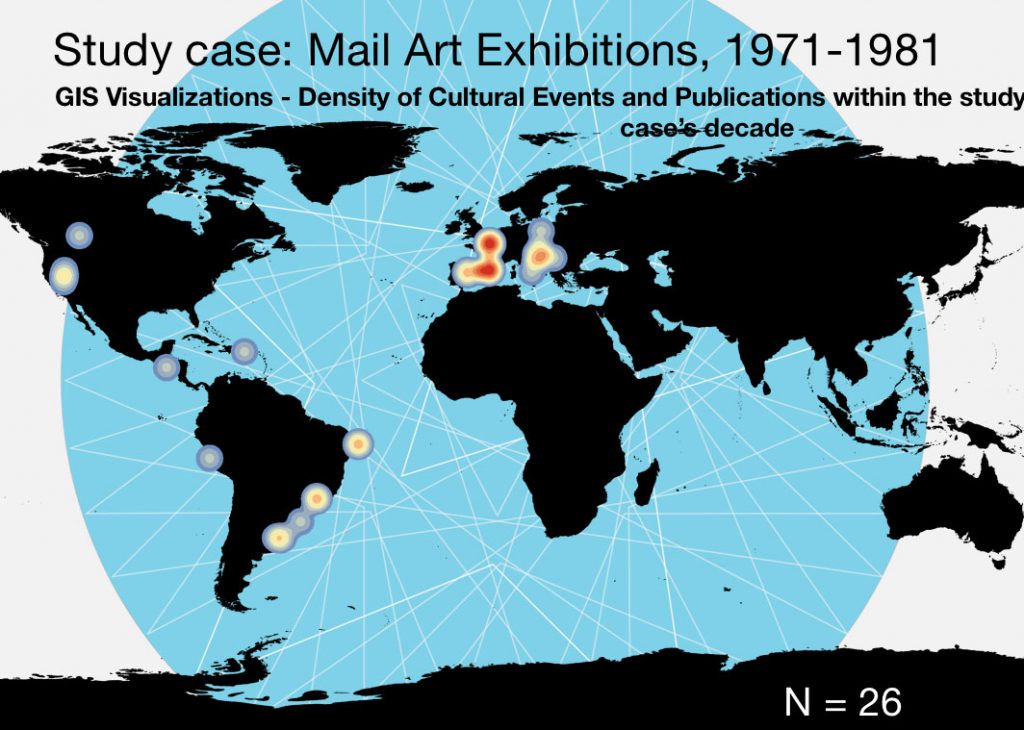

In order to map Mail Art practices, we introduced different sorts of events related to Mail Art in the database, focusing on the decade between 1971 and 1981. At this early stage, the reading and interpretation of this data do not pretend to be representative of the whole phenomenon; nevertheless, it illustrates the way we are envisioning our work with data visualization, and produce some preliminary comments. All the visualizations have been produced by our GIS specialist, Oscar Cambra Moo.

The first objective was to identify the places where exhibitions took place, and observe the way Mail Art practices developed and spread over the 1970s decade, in order to identify differences and similarities across the borders.

Being able to distinguish different types of events and productions allows us to reflect on the expansion of this practice and its institutionalization.

From a world perspective, GIS also allows us to zoom in on specific areas or countries related to our research interests.

With a study of events density it is possible to articulate a first hypothesis: the idea of decentralization of the famous New York-Paris axis, which was determining for the spread and definition of the artistic avant-gardes.

The first map below shows all the data within the database, including all the categories (historical, cultural event, artistic project and publication);

In the second one, all the data within the decade 1971-81, including cultural and historical events;

The third map shows only the events related to Mail Art, showing a more decentralized perspective. This study of density highlights the fact that artistic practices were taking place out of the North-North axis.

Questions raised by mapping cultural practices and events through GIS

Combined with the collection of two sorts of data – factual and interpretative -, the mapping of Mail Art exhibitions through GIS contributes to producing a multifaceted analysis, especially when dealing with non conventional artistic practices (non object-based, ephemeral, characterized by its circulation through networks, not fitting within traditional systems of classification and hierarchies, relying on immaterial aspects).

Following Anna Brzyski’s reflection on the potential of considering art history as “a synchronic and diachronic mapping system” rather than a narrative, we are particularly interested in exploring the potential of mapping as multilayered visual and conceptual alternative to a linear conception of history.[1]

Using digital resources to map countercultural practices: First conclusions

We shouldn’t forget that the use of digital means undoubtedly raises some pitfalls, which importance shouldn’t be overlooked: for instance, the risk to convert these geographical tools into authoritarian systems of classification, producing new categories of exclusion and inclusion (Irit Rogoff);[2] as Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel observed, “Maps do lie” and by no way we should consider the knowledge they produce as objective and truthful.[3] Rather, it must be addressed as a mutable working matter, the produce of a series of hypotheses, to be contextualized and completed (or contrasted) with other kinds of information.

Among the contributions digital means (either Databases and Geographic Information Systems) bring to our study:

– By combining different forms of organization (through search filters) and visualization (through mapping) of data, it is possible to work on a variety of scales: micro- and macro, situating local phenomena and practices within a global context.

– Embracing a wide range of objects and subjects of study (from artworks to publications, events, meetings, discoveries) and as such, they allow to address non-material elements and cross them with others.

– Changing the epistemological approach to our objects of study: developing a reflection through mapping instead of reading.

– Questioning the national paradigm applied to Art History and formulating alternative views to it.

– Producing diachronic and synchronic views, according to specific questionings.

– Making more visible the displacements, connections and trajectories of agents and objects.

– Connecting the transatlantic axis with a global scenario, highlighting new connections not necessarily mediated by the centres of artistic production or the places of political significance.

-Crossing cultural event and artistic production with geopolitical (social movements, technological

– Regarding the specificity of the Cold War period, digital humanities can be used to study a period in which technology experienced a huge evolution, as it developed at a great pace and was determining for the relationships between nation states, as well as political and cultural actors.

At last, we would like to insist on an aspect that might seem elementary and obvious, but which, in fact, must be acknowledged as it will have a great impact on the way our discipline of art history will keep on being constructed, questioned and transformed: digital means allow us to share, discuss and learn from others (colleagues, professionals of the cultural field, protagonists of the events we study, public) as never before. It facilitates collective processes of producing, learning, revising knowledge and as such, it represents a radically new paradigm in the way art is contemplated and included into narratives (but you could also say “maps” instead of narratives). In fact, this is not about stopping producing narratives/ or maps; it is about producing narratives/maps that operate an open plural and multifocal field of analysis.

With this in mind, we consider that a situated application of digital resources to art historiography undoubtedly brings significant and unforeseen results, encouraging to explore the challenging process of mapping and crossing cultural historical data.

[1] Brzyski, Anna (ed.), Partisan Canons, Durham : Duke University Press, 2007, p.18

[2] Rogoff, Irit. Terra Infirma. Geography’s Visual Culture, London: Routledge, 2000.

[3] Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice, “Introduction: Do Maps Lie?”, Artl@s Bulletin, no. 2 (2013): Article 1.