1. Presentation of the case study

Regina Silveira (1939) and Julio Plaza (1938) are two artists whose artistic careers are intertwined. Both had a traditional, academic training, but their practices were strongly influenced by the experiments that characterized the period. From painting and sculpture in the case of Plaza, and drawing, painting and engraving in the case of Silveira, their work suffered a shift towards the intermedia. Such changes, both in the materialization of their practices and in the contents and media, brought them closer to visual poetry, conceptualisms, and media experimentation with new technologies. Both developed a great interest in research and teaching: Regina Silveira started her teaching career in 1964; Julio Plaza, although he did so a little later in the early 1970s, pursued an academic career parallel to that of Silveira.

Their case is relevant for the study of transatlantic relational networks, considering the fact that both artists have received scholarships for international studies. Regina Silveira arrived to Madrid in 1967 with a scholarship from the Instituto de Cultura Hispánica (ICH); shortly thereafter, Julio Plaza arrived to Brazil with a scholarship from the Itamaraty [1]. Both artists met in Madrid, starting a joint path during the period covered by the present survey. During the 1960’s, 70’s and 80’s they maintained a personal relationship, and their trajectories coincided to a great extent because of it.

In Madrid, Silveira studied Art History at the Faculty of Philosophy and Arts. Rather than remaining in a high school with other foreign students, she preferred to meet local agents. She met Julio Plaza and the artists of the Grupo Castilla, founded in 1963 [2], as well as art and literature critics such as Ángel Crespo and Pilar Gómez Bedate, among others. This cultural nucleus was working theoretically and plastically towards interdisciplinary experimentation. It combined geometric abstraction, concrete and experimental poetry, new means of production and critique of the context [3]. That environment would be of great importance for both artists: while Plaza was at the centre of this artistic phenomenon in the Spanish capital, for Regina the discovery of such approaches in art was a point of transformation in her practices.

With regard to the context, the historical moment within which the encounter between Plaza and Silveira took place should not be overlooked. Both Brazil and Spain were under dictatorships, with repressive and fascist tendencies. This partly explains both artists’ need for mobility: the social environment was tense. Likewise, their movements report on a common interest in seeking new contexts and practices with which to elude national artistic systems that were underdeveloped and controlled by the centralist powers. From a broader perspective, both dictatorships were inserted in the period of the Cold War, in which the two opposing superpowers’ dispute for the international public sphere gave relevance to the states’ control of propaganda both inside and outside their territories. In this way, Brazil and Spain created institutions for the improvement of their image abroad. Culture, science and research were a very appropriate field for this [4], and in line with U.S. foreign policies, academic exchange programs were created in these countries, both by the Itamaraty and the Instituto de Cultura Hispánica (ICH).

In 1967 Julio Plaza travelled to Brazil in the same boat as his artworks, which were to be exhibited at the IX São Paulo Biennial. He had obtained a scholarship to study at the Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro. A few months later, Regina Silveira returned to the University of Rio Grande do Sul, where she was a teacher, and after a brief period between São Paulo and Porto Alegre, both artists were invited by Ángel Crespo to join the team of the School of Arts of the University of Puerto Rico at the Mayagüez Campus. Since then, their trajectories got intertwined in an almost indissoluble way: they travelled together to New York, visiting the exhibition “Information” (1971) at the MOMA; to the Encuentros de Pamplona (1972), to which Plaza participated; they teached at the University of Puerto Rico and, in 1973, upon their return to Brazil, were both professors at the Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado (FAAP) and the Escola de Comunicações e Artes of the Universidade de São Paulo (ECA-USP).

Silveira and Plaza began their careers in very distant territories, but due to the possibility—and the need—of international mobility, they developed artistic trajectories that intersected. The starting hypothesis of this visual survey implies a parallelism between both artistic contexts, based on a double relationship between these artists and their contexts: on the one hand, both are impelled to travel due to the dictatorial environment of their places of origin; on the other, these dictatorships, in their attempts to instrumentalise the field of culture under propagandistic premises, facilitated transatlantic encounters. Finally, a third parallel would be their shared artistic interests, rooted in Madrid’s cultural, critical and experimental environment where both artists met [5]. The objective of this survey is to visualize the trajectories of both artists through maps and diagrams, in order to make the starting hypothesis visible through a joint visual analysis of the trajectories of Regina Silveira and Julio Plaza.

2. Visualization methodology

Two types of representations have been chosen to visually evaluate the vital trajectories of both artists in the period of study: node diagrams and trajectory maps.

Node diagrams

They provide a visual overview of the interaction between the places visited by Silveira and Plaza and the years that make up the period of study, from the artists’ birth to 1982. By linking the size of the nodes to the number of actions registered in each place and year, we obtain information on which of them played a major role in the artists’ careers.

Trajectory maps

They show the artists’ “real” route across the globe. The reading of the maps has been facilitated by the adoption of a gradient colour code, from artists’ birthdates (red colour) to 1982 (blue colour). Likewise, for a better reading, those data that do not imply an effective displacement of the artist or his/her work have been eliminated. In this way, an exhibition carried out in a place of residence will not be visible, as it does not imply spatial displacement; in change, an exhibition out of the artist’s place of residence to which only his/her work travelled will be rendered on the map. Furthermore, a distinction is made between two types of movements: those that implied a displacement of the place of residence (continuous line), and those that were temporary (discontinuous line).

The following steps have been carried out in order to elaborate these visualizations:

- Research of biographical information. The data needed to carry out the visualizations have been obtained from different catalogues about the work and trajectory of both artists. Also of interest have been different details and comments provided in interviews with Regina Silveira [6]. The following categories have been used:

- Travel

- Training

- Teaching

- Artistic practice (significant projects, exhibitions and/or curatorial works)

- Data entry to the database.

- Data exportation

- Revision, filtering and debugging of data. Unification of criteria by columns: ‘Year’, ‘Place 1’, ‘Coordinates 1’, ‘Place 2’, ‘Coordinates 2’, ‘Event’, ‘Description’.

- Julio Plaza: 63 data rows.

- Regina Silveira: 51 data rows.

- TOTAL: 798 data fields.

- Data importation to the online tool Palladio (http://hdlab.stanford.edu/palladio/) developed by Stanford University.

- Execution of the visualizations.

- Node diagrams

- Maps

- Updating the visualizations with vector graphics editing tools. Creation of a colour code to clarify the visualization. Insertion of captions.

3. Preliminary analysis of the visualizations

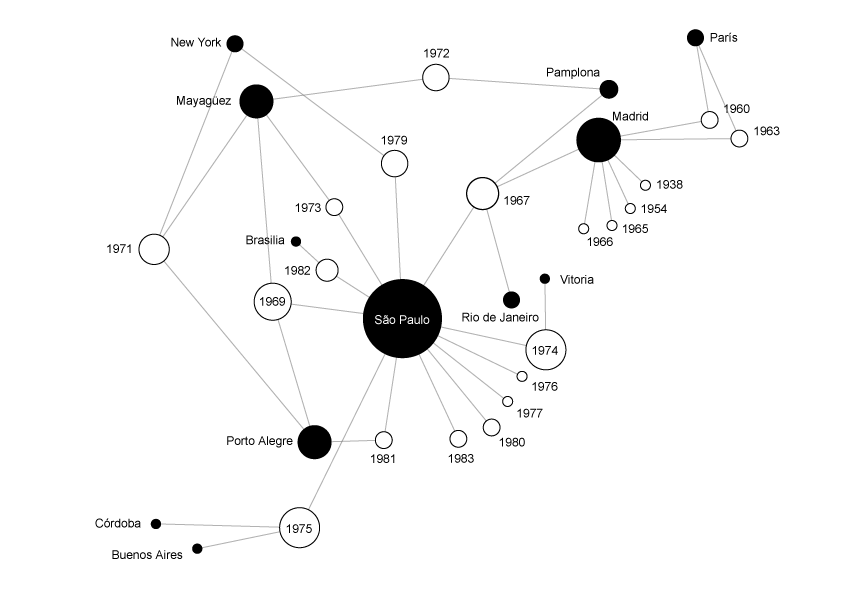

Figure 1 – Node diagram of places and years that shows the relevance of the time and space nuclei in the initial artistic trajectory of Julio Plaza. The size of the nodes is related to the number of activities recorder for each given year or place, prioritizing to the visualization of the amount of activities carried out in each location and moment.

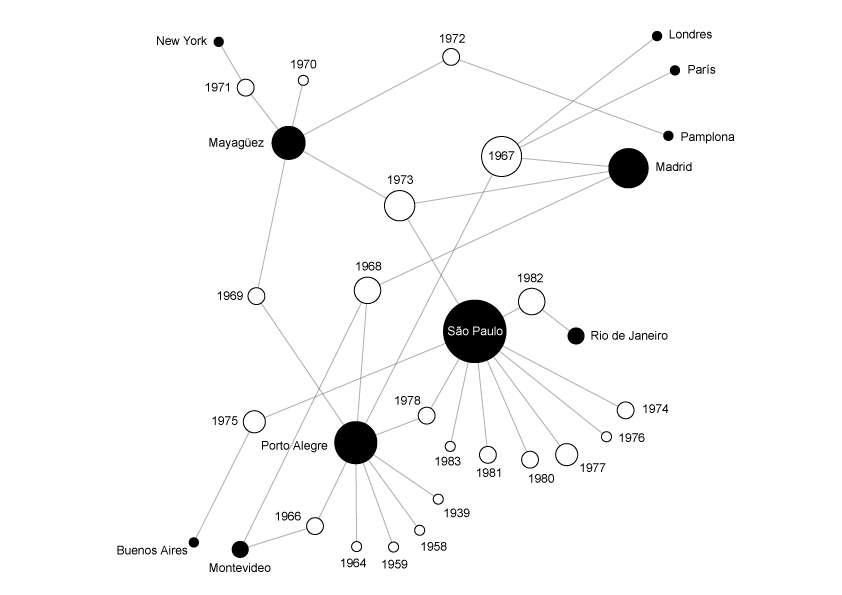

Figure 2 – Diagram of nodes of places and years showing the relevance of the time and space nuclei in Regina Silveira’s initial artistic trajectory. The size of the nodes is related to the number of activities recorded for each given year or place, prioritizing the visualization of the amount of activities carried out in each location and moment.

Despite Silveira’s and Plaza’s distant origins, the revision of the node diagrams highlights the coincidence of places where both developed their artistic and professional practices until 1982. In both diagrams we can appreciate the relevance of the same four geographical points. At the same time similarities in the relative importance that each place had in the trajectory of both artists are also highlighted. These places are, in order of importance:

- São Paulo: Place where both artists settled down in 1973, and where they carried out a great part of their artistic work and teaching work.

- Madrid y Porto Alegre: Places of origin of Plaza and Silveira, respectively. Both have a similar importance in the first stages of the trajectories of the two artists, with specific actions later. Nevertheless, it is possible to appreciate how Porto Alegre takes on a slightly greater dimension in Silveira’s trajectory, just as Madrid does in Plaza.

- Mayagüez: A place of the same importance for both artists, where they were enrolled in the School of Arts at the University of Puerto Rico, invited by Ángel Crespo in 1969.

Other similarities of lesser rank are also found in the places apparently of lesser importance in these artists’ trajectories. The cities of Paris, New York, Buenos Aires and Rio de Janeiro, all cultural nuclei, were visited by Plaza and Silveira.

Regarding the examination of transatlantic crossings, in the case of Regina Silveira’s diagram we can observe the Madrid-Porto Alegre axis mediated by 1967, when she received the ICH scholarship. At that moment she came into contact with the experimental artistic nucleus of Madrid, and with Julio Plaza. In the case of Plaza, the transatlantic connection is observed that same year, with the trifurcation Madrid-Rio de Janeiro-São Paulo. That year his work travelled to the São Paulo Biennial, at the same time he established himself at the Escola Superior de Desenho Industrial (ESDI) in Rio de Janeiro. It can also be observed that Plaza only connected with Porto Alegre in 1969, once he had met with Silveira in Brazil. By this time, the interweaving produced by their scholarships had already had an effect. From then on, their trajectories practically overlap. It can be inferred that the crossed scholarships provided by Itamaraty and the ICH were the catalyst for the interweaving of their professional and artistic practices.

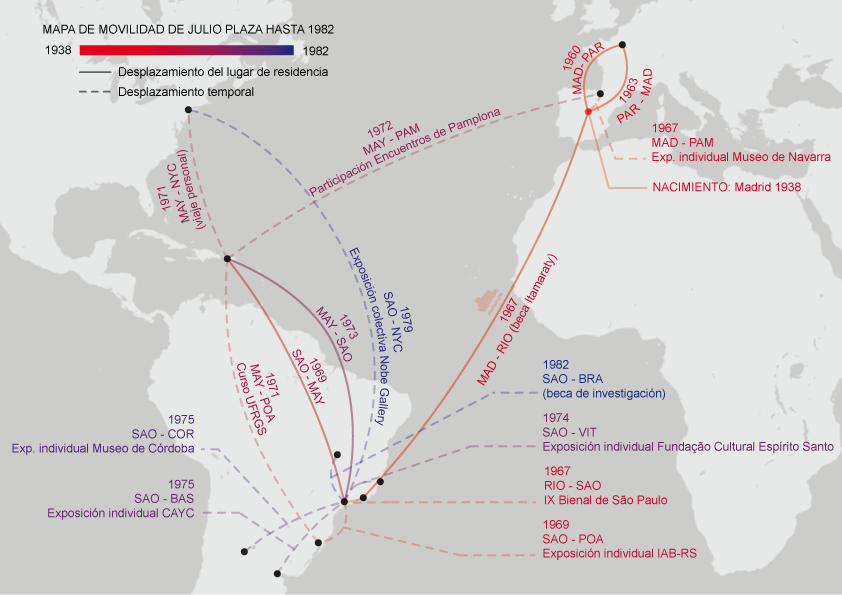

Figure 3 – Trajectory map showing Julio Plaza’s routes at the beginning of his artistic career. It allows to visualize the network of journeys and displacements, with particular emphasis on the network produced rather than on the number of activities carried out in each place.

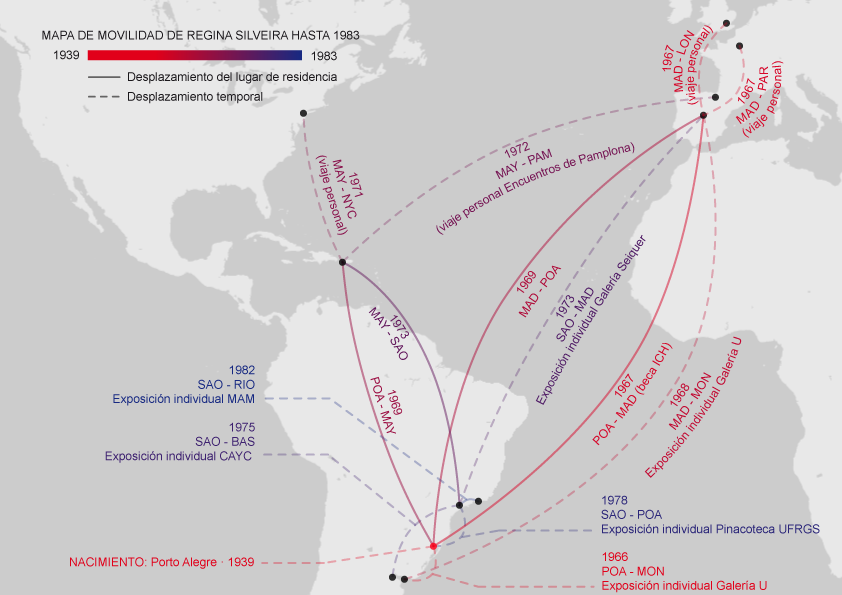

Figure 4 – Trajectory map showing Regina Silveira’s routes at the beginning of her artistic career. It allows to visualize the network of journeys and displacements, with particular emphasis on the network produced rather than on the number of activities carried out in each place.

The analysis of the node diagrams is confirmed by the review of the trajectory maps. In a more detailed way, the same conclusions can be drawn regarding the intersections of both artistic trajectories, but paying more attention to mobility than to the number of activities at each time and place. In this case, the amount of information is greater and makes possible to know not only the year and the geographical relation, but also the motive behind the most relevant displacements. The captions, the colour code and the dashed lines —see point 2 of this study, “Methodology of visualization”— help to read the maps, allowing to perceive in a single glance the similarity of the routes and trajectories of Silveira and Plaza. At the same time the information provided about the routes is extended in an attentive second reading.

It is important to point out that, as already noted, since the trajectory maps focus more on mobility than on the number of activities carried out in each place, the relative importance of the geographical nuclei is more dissolved in them than in the node diagrams. However, it is possible to analyse in these maps the precise trajectories, with a spatial exactness that the node diagrams do not allow. Thus, São Paulo, Madrid, Porto Alegre and Mayagüez are inserted in a wider network of spatial relations, which significantly has the same formal aspect in the trajectory maps of both artists.

4. Bibliography

Arte Objetivo. Madrid: Sala de exposiciones de la Dirección General de Bellas Artes, 1967.

Grupo Castilla 63. Madrid: Gráficas Nebrija, 1965.

Julio Plaza. Poética / Política. Porto Alegre: Fundação Vera Chaves Barcellos, 2013.

Luz Lumen. Regina Silveira. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2005.

Regina Silveira. Milán: Edizioni Charta, 2011.

Regina Silveira. A lição. São Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, 2002.

Regina Silveira. Umbrales. Madrid: Galería Metta, 2008.

Revista de cultura brasileña. Madrid: Embajada de Brasil en Madrid, 1962.

BARREIRO, Paula. La abstracción geométrica en España (1957-1969). Madrid: CSIC, 2009.

IBER, Patrick. Neither Peace nor Freedom. The Cultural Cold War in Latin America. Cambridge, Londres: Harvard University Press, 2015.

—

[1] The Itamaraty is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Brazil.

[2] Elena Asins, Onésimo Anciones, Luís García Núñez (Lúgán), Miguel Pinto, Julio Plaza, Manuel Prior and Víctor Ventura. See AREÁN, Carlos Antonio. “Grupo Castilla 63”, in: Grupo Castilla 63. Madrid: Gráficas Nebrija, 1965, n.p.

[3] For an analysis of that environment and, specifically, of Julio Plaza’s posture, see BARREIRO, Paula. La abstracción geométrica en España (1957-1969). Madrid: CSIC, 2009, 325. See also the text by Ángel Crespo for the exhibition “Arte objetivo”, Arte Objetivo. Madrid: Sala de exposiciones de la Dirección General de Bellas Artes, 1967, n.p. Catalogue of the exhibition.

[4] For an analysis of this international context, see IBER, Patrick. “Modernizing Cultural Freedom”, in: Neither Peace nor Freedom. The Cultural Cold War in Latin America. Cambridge, London: Harvard University Press, 2015, 174-210.

[5] The cultural milieu in Madrid had an important relationship with the arts in Brazil. Ángel Crespo, a critic closely related to Regina Silveira and Julio Plaza, edited the Revista de Cultura Brasileña between June 1962 and December 1969. Through it he came into contact with Brazilian poetry and experimental art, helping its diffusion in Spain. Julio Plaza later collaborated with Augusto de Campos, for example in the Poemóbiles (1974). One detail is significant for the scope of this work: the first 12 issues of the journal were published “por el servicio de Propaganda y Expansión Comercial de la Embajada de Brasil en Madrid [by the Propaganda and Commercial Expansion Service of the Brazilian Embassy in Madrid]”. From number 13 onwards, any reference to ‘propaganda’ was eliminated, and it was simply read that the magazine was “editada por la Embajada de Brasil en Madrid [edited by the Brazilian Embassy in Madrid]”. See Revista de cultura brasileña. Madrid: Servicio de Propaganda y Expansión Comercial de la Embajada de Brasil en Madrid, 1962. Volume IV, number 12, March 1965. See also Revista de cultura brasileña. Madrid: Embassy of Brazil in Madrid, 1962. Volume IV, number 13, June 1965.

[6] Interviews with the artist done by the author of this study, on various dates. Special thanks to Regina Silveira for her disposition and kindness.

—

Front picture: Aaron Gustafson, Poemobiles by Augusto de Campos & Julio Plaza, 2008. (CC BY-SA 2.0)