1. Presentation of the case study

Vicente Aguilera Cerni (Valencia, 1920-2005) is one of the Spanish art critics and historians of the 20th century with the greatest international projection. He embodies the Spanish militant critic of his time. The aim of this case study is to highlight the impact of his publications beyond national borders and try to analyze how their subjects and themes have been distributed over time and countries.

Aguilera was an autodidact, his first texts were published in 1953, and in 1954 he started to work as a researcher on art from the Middle Ages. He soon started to publish studies on American art, given that the US information service supported his career between 1954-1959: he was in charge of giving lectures in his numerous centers in Spain (the American Houses), published in their media and even formed part of their management team[1]. In 1956 he started to coordinate the Parpalló Group, which survived until 1961, and coined the concept of normative art.

His career culminated in the following years, between 1959 and 1964, when he gradually showed his political commitment to the ranks of the left. A very relevant fact in his biography is the reception of the Critics’ Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1959, which catapulted his career and gave him an international dimension. After his award, the regime commissioned some projects to him, such as curating the Spanish participation at the III Biennial of Alexandria. He was involved in the debate regarding the regime’s promotion of contemporary art.

Between 1962-1967, he directed the magazine Suma y sigue del arte contemporáneo , an authentic platform for international exchange from which he supported normative art and then, the new forms of social and critical realism. In 1965 he defined the term “Crónica de la Realidad” (Chronicle of Reality), advocating a painting that combined features of pop with social content. This term is still in use today.

During these years, between 1961 and 1965 and then in 1967, he took part in the most important meetings for European engaged art critics, the Rimini conferences, directed by Giulio Carlo Argan, which were also expressed in the San Marino Biennials. Aguilera brought to Spain the ideas discussed in Rimini (the alternative to informalism, the relationship between art and science) and encouraged Spanish artists to take part in these conclaves. In terms of critique, he contributed to the creation of a Spanish national section of critics within an international organization such as AICA.

Vicente Aguilera was in charge of encouraging some Spanish artists to participate in the mythical exhibition España Libre (1964-65) held in Italy, in which art was shown out of the control of the regime. We can see that he adopted a position of militant critic, as opposed to his position only three years before, more ambiguous.

Between 1965 and 1976 Aguilera developed a series of projects in which he already took some distance with the regime[2].In 1965, he participated in the World Congress for Peace in Helsinki, organized by the international department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. In a few years, he went from being a friend of American imperialism to being a companion of the communists.

On a professional level, he published in 1966 what is probably his most frequently quoted work Panorama del nuevo arte español(Panorama of New Spanish Art) [3], in which he considered art from 1940 to 1966. The same year he published Ortega y D’Ors en la cultura artística española (Ortega and D’Ors in Spanish Artistic Culture) [4], and shortly after em>Iniciación al arte español de la postguerra (Initiation to Spanish Post-War Art) [5], as well as several books bringing together a selection of his articles, among many other publications, articles and texts for catalogues[6].

A little-known fact was the commission by the Ministry of Education and Science of at least six scripts for art documentaries between 1966 and 1971.

During these years, Aguilera generated several innovative projects, such as the experiment called Antes del arte entre 1968-1969 (Before Art between 1968-1969), in which he explored the relations between art and science. He founded a museum in the small town of Villafamés (province of Castellón), which opened to the public in 1972, .

Years went by, Aguilera was disappointed after the repression of the Prague Spring and decided to join the project of Professor Tierno Galván. His political commitment led him to become president of the Partido Socialista Popular-PV between 1975 and 1978.

1975 was a turning point, with two events that put Aguilera in a delicate situation: the hiring of another team of professionals – led by Tomàs Llorens and Valeriano Bozal – for the Spanish exhibition at the 1976 Venice Biennale. The other event was his participation in the organizing committee of the exhibition promoted by the Valencia City Council entitled 75 años de pintura valenciana (75 years of Valencian painting), against which the artists spoke out because it was still a proposal of the regime.

As a consequence, he lost the position of leader but remained active almost until 2005. He directed the Historia General del arte valenciano (General History of Valencian Art) in 6 volumes (1986), a work that still remains unsurpassable in the field. Between 1979 and 2003 he edited the third magazine of his career, Cimal, a benchmark in contemporary visual culture. He was appointed adviser for culture within the ranks of socialism in 1981, and was required for a consultative body called Consell Valencià de Cultura since 1985, holding his presidency between 1994-96. At the same time, he was excluded from the projects that the new cultural structures are setting in motion. In the last years of his life he received awards and institutional recognition but the generation of the Transition, both critics and artists, did not appreciate or see in him the figure of the intellectual.

The objective of this study is to reach a series of conclusions on the impact of the production of Vicente Aguilera through the visualization of data in maps and ideograms. First, we want to evaluate whether Aguilera’s publications are international in scope. On the other hand, we will try to show whether or not there are differences between the subjects on which he publishes in Francoist Spain and abroad. Finally, we will carry out an analysis of the publishers that supported his work.

2.Visualization Methodology

The following actions have been carried out to study the impact of this critic’s work:

- Introduction in the MoDe(s) database of all the bibliography written and published by Vicente Aguilera Cerni throughout his life, from 1953, the date of his first writings, until his death in 2005, assigning categories of key concepts. Books, catalogues, articles and press have been included. A total of 383 bibliographic records written by Aguilera have been introduced. Each bibliographic record has been introduced with latitude and longitude references.

- Data export; review and debugging of records in different tables.

- Transfer of the data to the Palladio tool, a Stanford University program (https://hdlab.stanford.edu/palladio/) that allows the visualization of data in maps and their sequencing in temporal layers on the maps. It also offers the visualization of data in tables, diagrams of nodes, etc.

- Selection of specific maps that facilitate new analyses and readings that provide greater knowledge.

- Establishment of legends for the interpretation of the maps.

The following visualizations of data have been selected:

Location map of publications

In the location map it is possible to see the geographical scope of Aguilera’s publications.

Diagrams of nodes

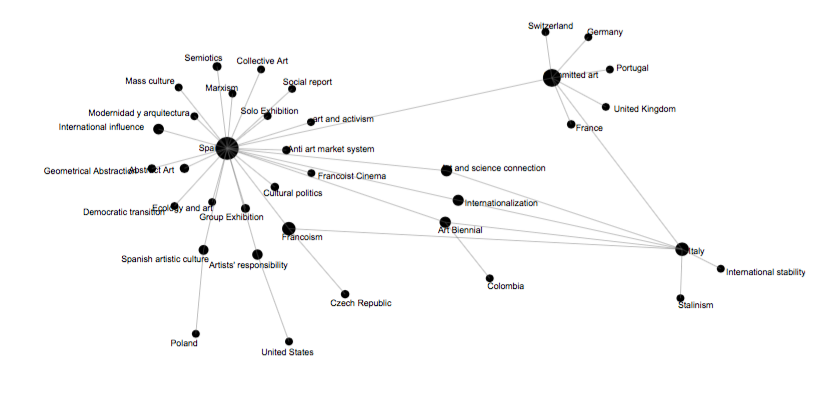

The diagrams of nodes connects the countries where he published his texts with the concepts. The major nodes present the most frequently repeated themes.

3. Preliminary analysis of visualizations

This map allows us to observe the locations of all the texts published by Aguilera and we can affirm that it had an international scope. The nodes of greater volume indicate the countries where the number of published texts is greater. In addition to Spain and Italy as main nuclei, there are publications in other parts of Europe such as France, Germany, Portugal, Switzerland or Great Britain among others, and writings in the USA and Colombia. This international scope is appears more frequently until 1975 and decreases after that date.

We want to know if there is any relationship between the topics and the different countries in which he published throughout his career. To analyze it, we considered important to separate the information into two diagrams of different nodes that allow us to visualize this thematic relation in two temporal sequences: one that covers the period until 1975, and another from 1976 onwards. This separation allows us to compare which subjects Aguilera decided not to publish in Francoist Spain and which one were published abroad.

This graph shows the relationship until 1975. The thickest nodes indicate the subjects with the greatest number of bibliographic records. We see that both committed art and Francoism were the most reiterated themes in the production inside and outside borders. And subjects such as international stability, criticism of the system, dissidence, transnational collaboration or Stalinism were the ones he prefered to deal with in foreign publications and not within the peninsula. Whenever he published outside Spain, in Germany, Portugal, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, he tackled issues such as the artist’s commitment or ethical responsibility[7].

We see that its production is now concentrated in Spain and Italy. We can see that the idea of compromise is constant in his writings throughout his career. What topics exist now, that did not exist before the fall of the regime? He deals with the Civil War, the idea of democracy, technological development, the atomic bomb, social movements, public space and solidarity with Chile.

Palladio allows you to view the articles grouped by journals in which they were published. This has allowed us to observe a distribution of Aguilera’s subjects among the periodical publications, a reading that can be lost in a broader view of the critic and historian’s large production. From this group we can see that the subjects he dealt with in the magazine Realidad (cultural organ in exile of the PCE, in which he wrote for example about the social function of Picasso) were subjects he did not publish about in Archivo de Arte Valenciano (the magazine of the Real Academia de San Carlos de Valencia, in which he published about medieval art or local current affairs), or from Suma y Sigue del arte contemporáneo(where he talked about the defence of realism and international information), to give just a few examples. The themes are distributed in a wide range of magazines and are clearly in tune with the line or positioning of each magazine.[8]

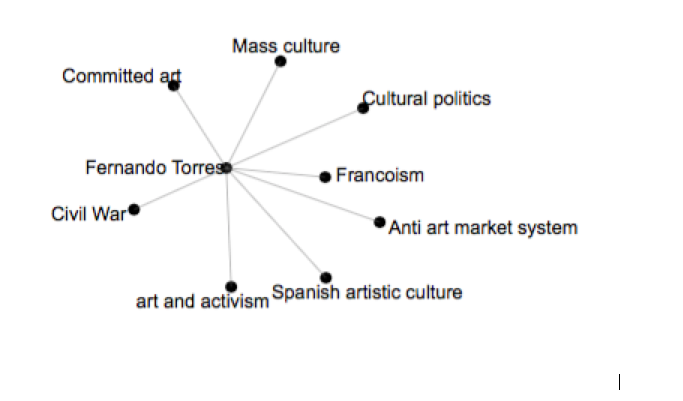

We can also draw some conclusions about the publishers who published his texts. Throughout his public life, both in the public and private spheres. His texts were published in catalogues by multiple galleries inside and outside Spain. As for the books, they were printed by commercial publishers inside and outside the country, mainly in Spain and Italy. There is an enormous dispersion in the publishing houses with which he worked. They almost always published him on one or two occasions: Guadarrama, Ciencia Nueva, Cuadernos para el diálogo, Mas-Ivars…, with the exception of the publishing house Fomento de Cultura, which published its first three books, and with Fernando Torres, who published a dozen of his works. [9]

Fernando Torres was married to Aguilera’s daughter, his son-in-law. This possibly explains why Aguilera felt comfortable and chose to work with his publisher.

If we look at the focus of his books we will see that, broadly speaking, the ones published in more commercial publishing areas have less critical positioning; in large publishing houses such as Polígrafa or Capelli, the subjects have a more international perspective and a panoramic review; the institutional commissions he undertook were often artists’ monographs or compendiums of documents (such as the one commissioned by the Ministry of Education and Science in 1975). We find the works with greatest reflection and historical effort in publishers with lines of work that value research quality, such as Panorama del nuevo arte español (Madrid, Guadarrama, 1966), Ortega y D’Ors en la cultura artística Española(Madrid, Ciencia Nueva, 1966) and similar. But in all of them, he maintained one constant: to point out the need for commitment from the critical and artistic spheres.

4. Bibliography

BARREIRO LÓPEZ, Paula, La abstracción geométrica en España (1957-1969), Madrid, CSIC, 2009.

——–, “El giro sociológico de la crítica de arte durante el tardofranquismo” in Jesús Carrillo y Jaime Vindel (eds.), Desacuerdos. Sobre arte, políticas y esfera pública en el Estado español, 8, Madrid, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía-MACBA, 2014, pp. 16-45.

——–, “Arte, ciencia y tecnología: Vicente Aguilera Cerni y Antes del Arte frente a las dos culturas” in AAVV, Colectivos artísticos en Valencia bajo el franquismo 1964-1976, Valencia, IVAM, 2015, pp. 234-244.

——–, Avant-garde Art and Criticism in Francoist Spain, Liverpool, Liverpool University Press, 2017.

FRASQUET BELLVER, Lydia, “Ética desde la resistencia: el compromiso político de Vicente Aguilera Cerni”, Archivo Español de Arte, 356, Madrid, 2016, pp. 409-422.

——–, El historiador y crítico Vicente Aguilera Cerni y el arte español contemporáneo, Departamento de Historia del Arte, Universitat de València, Valencia 2017.

Notes

[1] These statements are based on my doctoral thesis El historiador y crítico Vicente Aguilera Cerni y el arte español contemporáneo, Departamento de Historia del Arte, Universitat de València, Valencia 2017.

[2] Lydia Frasquet Bellver,“Ética desde la resistencia: el compromiso político de Vicente Aguilera Cerni”, Archivo Español de Arte, 356, Madrid, 2016, pp. 409-422.

[3] VAC, Panorama del nuevo arte español, Madrid, Guadarrama, 1966.

[4] VACVAC, Ortega y D’Ors en la cultura artística española, Madrid, Ciencia Nueva, 1966.

[5] VAC, Iniciación al arte español de la postguerra, Barcelona, Península, 1970.

[6] VAC, El arte impugnado,Madrid, Cuadernos para el diálogo, 1969. VAC, Posibilidad e imposibilidad del arte. Comentarios en el tiempo, Valencia, Fernando Torres, 1973.

[7] I’m referring, for example, to the demand for freedom in the Spanish cultural sphere that is carried out in “Sul significato di una cultura libera”, in AA.VV. Free Spain. Esposizione d’arte spagnola contemporane [Exhb. Cat.], Rimini, Palazzo dell’Arengo, Grafiche Gattei, 1964, s.p. He also denounces the trauma experienced by post-war Spain in the text “Contemporary Spanish painting and sculpture”, Contemporary Spanish painting and sculpture>[Exhb. Cat.], London, Marlborough Fine art and New London Gallery, 1962.

[8] Some examples are: while in the review Realidad publica “Sobre las posibilidades de comunicación de las artes visivas en las sociedades actuales” (7, Rome, November 1965) or the mentioned article “Picasso: la función y el ángel” (13, Rome, 1967), in the review Archivo de Arte Valencianopublica titles such as “En torno al problemático Jacomart” (25, Valencia, January-December 1954) and “Ante una tabla vicentina de Colantonio” (26, Valencia, January-December 1955). Another case is that of the more conservative review Punta Europa where he publishes “Manolo Millares” (12, Madrid, December 1956, pp. 118-121) and “España en la XXIX Bienal de Venecia” (33, Madrid, September 1958, pp. 134-139), while he leaves articles como “Marxismo y humanismo económico” (extraordinary, 10, Madrid, October 1968, p. 15.).for a more progressive platform such as Cuadernos para el diálogo.

[9] With the publisher Fernando Torres he will publish Porcar (1973), Posibilidad e imposibilidad del arte. Comentarios en el tiempo(1973), El arte en la sociedad contemporánea (1974), Alberto Sánchez: palabras de un escultor (1975), Arte y compromiso histórico (sobre el caso español) (1976), William Morris. Arte y sociedad industrial (1977) and Diccionario del arte moderno: conceptos, ideas, tendencias (1980).

Front picture: España Libre. Palazzo Strozzi, Florencia, otoño 1964. AHVAC (Archivo Herederos Vicente Aguilera Cerni)