International workshop

Partisan genealogies: counter-visualities since WWII

Université Grenoble Alpes

7 May 2020

by Anita Orzes

The international workshop Partisan genealogies: counter-visualities since WWII aimed to reflect on how exhibitions, archives, films, journal and visual production deal with the partisan imaginary. Following our research on the complex role of the oral, written and visual productions as agents for a culture of resistance, via different case studies that connect the Western World, the Socialist bloc, the Third World and the Non-aligned countries, this seminar was the second part of the workshop Partisan Resistance(s): a tool box for analysing transnational concepts and images (here the report) that took place in March.

It was structured by two sessions: the first, with the interventions of Gal Kirn, Paula Barreiro López, Jaime Vindel and Jacopo Galimberti, emphasized the figure of partisan; the second, with the interventions of Fabiola Martínez, Anita Orzes, Olga Fernández López and Sonia Kerfa, reflected on exhibitions and films as agents of resistance.

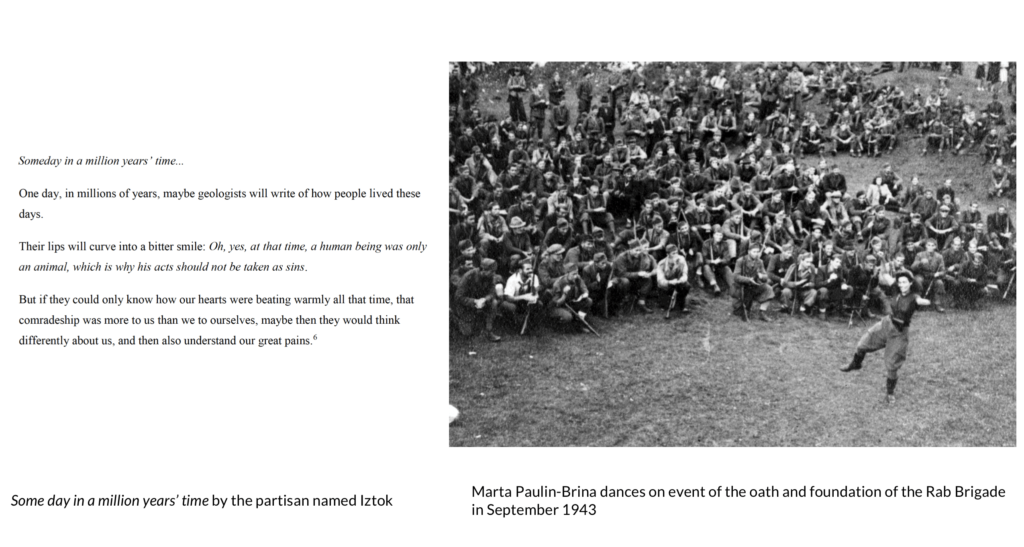

Gal Kirn presented a paper titled “The partisan counter archive: how to commemorate the rupture?” in which he retrieved emancipatory fragments and artworks from the Yugoslav partisan’s liberation struggle. Firstly, he explained the counter-archive as a space that includes works characterized by a high degree of (self)awareness, works that practiced a “sort of impossible revolutionary temporality”, but also works that could not easily be integrated in the Yugoslav socialist archives or in the post-socialist and nationalist archives. He then provided case studies, such as the poem “Someday in a million years” by a partisan named Iztok and a partisan dance by Marta Paulin-Brinda. If the poem stressed the contradictory relationship between the brutal Second World War moment (the transformation of man into “an animal” and the opposition between crimes and sins, perpetrators and victims) and the future (will people be able to understand the level of barbarism enforced in war times?); the dance of liberation of Paulin-Brinda, under the influence of the environment and the situation, shows how she developed “new” dance techniques and expressions in front of a partisan audience, while celebrating the liberation of the concentration camp on the island of Rab (occupied by Italy before of capitulation).

The following paper “Some preliminary thesis on the Partisan(e)s: Partisan Images and Culture Resistance” by Paula Barreiro López traced a broad panorama on the heterogeneity of partisan families across places (from the East to the West and from the West to the South) and times (connecting mostly the 1930s to the 1960s and 1970s). She stressed that the partisan fight was rooted in a revolutionary program of social justice and a reconfiguration of the political, economic and cultural structures. Thus, partisans were not only fighting for land and freedom, but also for liberation. Through two journals, Partisans and Tricontinental, it is possible to highlight the rehabilitation of the struggle as a revolutionary one, creating an imagined community that connected the revolutionary struggles around the world. A visual example of this is a cartoon by Siné (1961) that depicted the partisan spirit as a battle of the races of the world in a connected struggle through the interconnection of the fighters’ beards and hair, similarly to the way in which Rostsgaard depicted three interchangeable racialized faces with one body. Paula Barreiro also reflected on the question of the artist as partisan and the partisan artist with a large itinerary from France (Abdon a partisan and an artist in the mountains of Grenoble during the WWII), to Cuba (with Saul Steinberg’s caricature of an artist fighting with his paint brush and later on Julio Le Parc artwork “Identifique sus enemigos” (Identify your enemies), a proposition for the spectator to take down potential enemies, represented by the silhouettes of imperialist archetypes (the capitalist, the military, the priest or the Yankee).

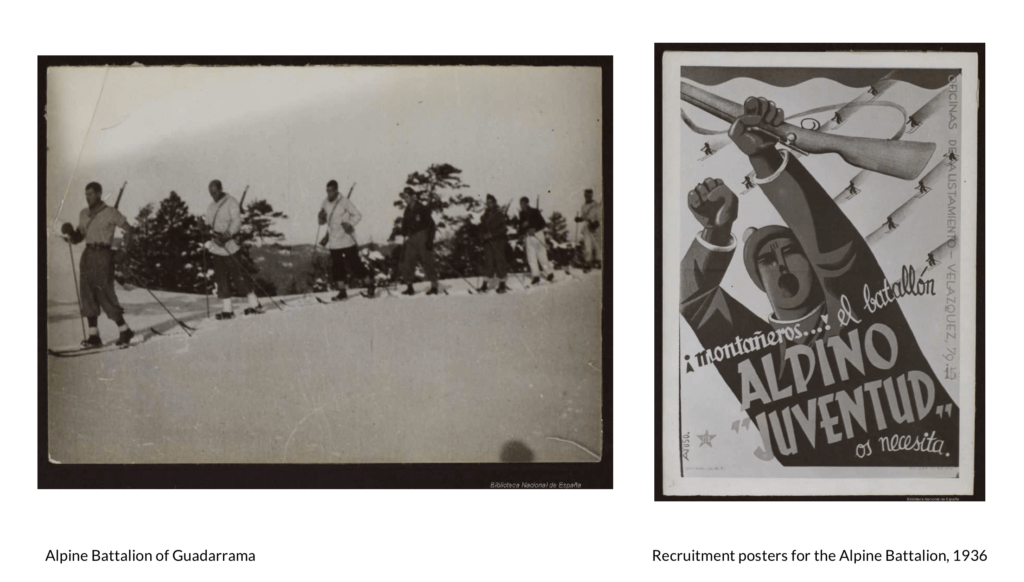

Her final reflection on the mountains as an example for a ‘lieu de résistance’ paved the way for the paper “Partisan ecologies: the politics of the wild after the end of the world” by Jaime Vindel. Defining the partisan ecology as “a geographical and existential expression of the class struggle, which would somehow prefigure the post-national and proletarian component that eco-social struggles should possess today”, he pointed out that the mountains represented a cosmopolitan meeting place for the partisan cultures of resistance analysing the graphic repertory of the Alpine Battalion of the Sierra de Guadarrama. Firstly, he illustrated the history of the Battalion and its visual archive. The Battalion was a unit created in September 1936, with a section integrated within the 5th Regiment of the People’s Militias and another made up of members from the Unified Socialist Youth, and composed by sportsmen with knowledge of skiing. Secondly, he compared the thesis on partisan ecologies by Andreas Malm (internationalist by definition) with the telluric one of Carl Schmidt, pointing out that the Alpine Battalion didn’t defend a territory invested with a telluric component but it “drew with a few bodies, a few sticks and a few skis the geography of resistance”. Finally, he went from the close past to the close present by addressing the suicide of the skier Blanca Fernández Ochoa, her trajectory and her relation which Cercedilla (the area where the Alpine Battalion operated). Jaime Vindel considers that sport paved the way to the integration of Franco’s/and post-Francoist Spain into the international arena of which Blanca Fernández Ochoa is one of its symbols, since she was the first Spanish sportswoman to win a medal in the winter Olympics of Albertville (1992). He wonders, “what dialectic image can compose today the semantic constellation between the visual archive of the Alpine battalion, the partisan ecologies of Malm and Fernández Ochoa´s suicide?”.

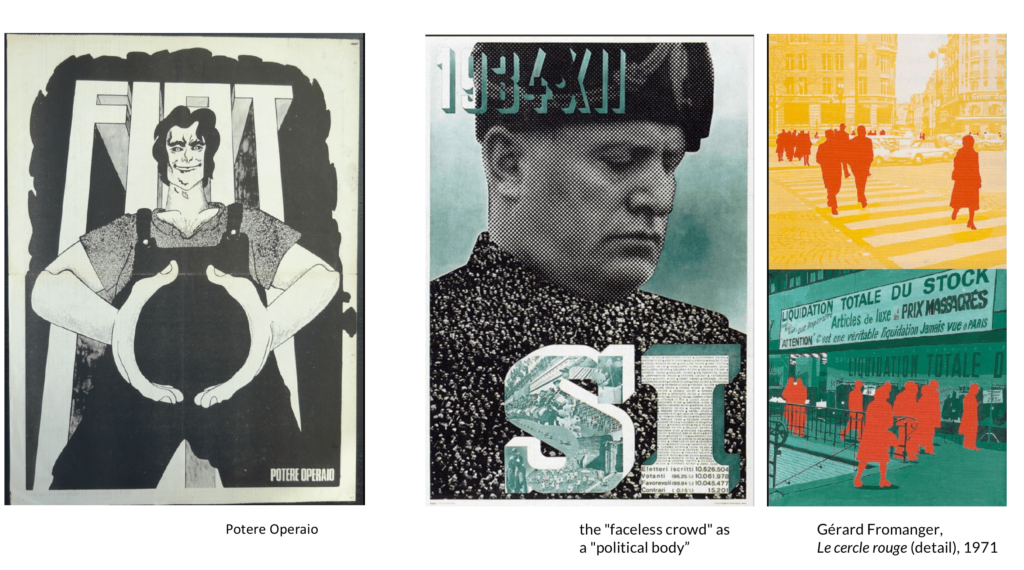

The last paper of the morning was “Le partisan, la partie maudite et le masque. Deux projets autour de l’imagerie de l’extrême gauche”. Jacopo Galimberti addressed two issues: the first one was the operaismo as opposed to the figure of the partisan, the second one was the anonymity of the partisan. In particular, he highlighted the political role of the mask as an object that makes you anonymous and therefore becomes a form of self-defence. After a historical overview of the operaismo movement in Italy in the 1960s, Jacopo explained that the operaismo was personified in the young worker who works in a factory and hated his job. This worker is built in opposition to two definitions of the partisan: the partisan as a patriot and the partisan as a guerrilla fighter. Through the analysis of a series of images by Mario Mariotti, emphasis was placed on how the worker fuses with his work tools. This allowed showing that for Potere Operaio the factories were understood as a battlefield, in an unarmed struggle. Galimberti highlighted this opposition as well with the armed struggle of Brigate Rosse which, through the iconography of the Third World, associated their struggle with that of the guerrillas in Latin America. Shifting the attention from Italy to Latin America, he introduced the figure of Subcomandante Marcos. This allowed him to point out some considerations about the “faceless crowd” from the 1960s to the 1980s: 1. the faceless crowd can take the form of an army; 2. the faceless crowd often appears in photographs of political meetings; 3. the faceless crowd finds its place within a political symbol, in the proximity of the leaders (represented then on a larger scale) or even in the members of their bodies, thus forming a “political body”. After having presented several examples, from Italy, the Soviet Union, Spain and France, Galimberti wondered where this international imagination comes from, asking what redefines the link between identity and face, and transforms anonymity into a form of self-defence.

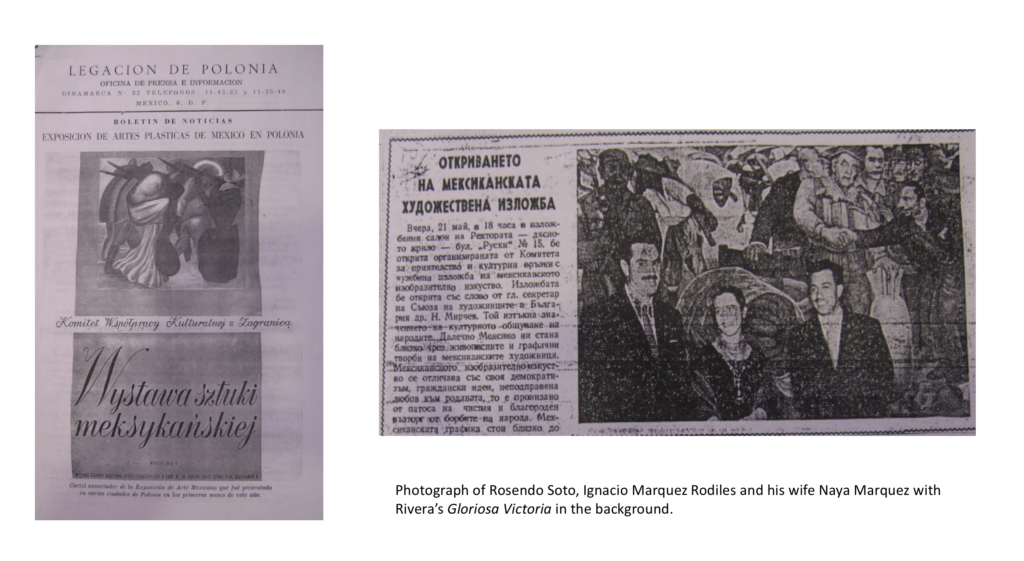

The afternoon session opened with the paper “Mexican art in the Eastern Block: The partisan aesthetic of the Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas” by Fabiola Martínez. She analysed an exhibition of Mexican art organized by the Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas (FNAP) which toured cities in the Easter Block between 1955 and 1956 (starting in Warsaw and finishing in China). After pointing out, firstly, the complex dynamics between the Mexican School and the Mexican Government and, secondly, that the Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas (1951) was used by the Mexican School as a way to rekindle the spirit of the revolution, and subvert US imperialism in Mexico and abroad, Fabiola Martínez explained that the exhibition was commissioned by the Polish Committee for Cultural Relations in direct relation with the FNAP (instead of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes/INBA, the official organ in charge of organizing international exhibitions); the invitation directly to FNAP would ensure no governmental censorship. After having presented the political context, she offered a view on some of the artworks exhibited, such as Nuestra imagen actual (1947) by David Alfaro Siqueiros or Fusilamiento (1950) by Leopoldo Méndez. Finally, she contextualized the artworks within the inaugural speech of Rosendo Soto, in which he highlighted the divergence of the Mexican aesthetics from socialist realism, by defining Mexican aesthetics as an art of denunciation not of propaganda[1].

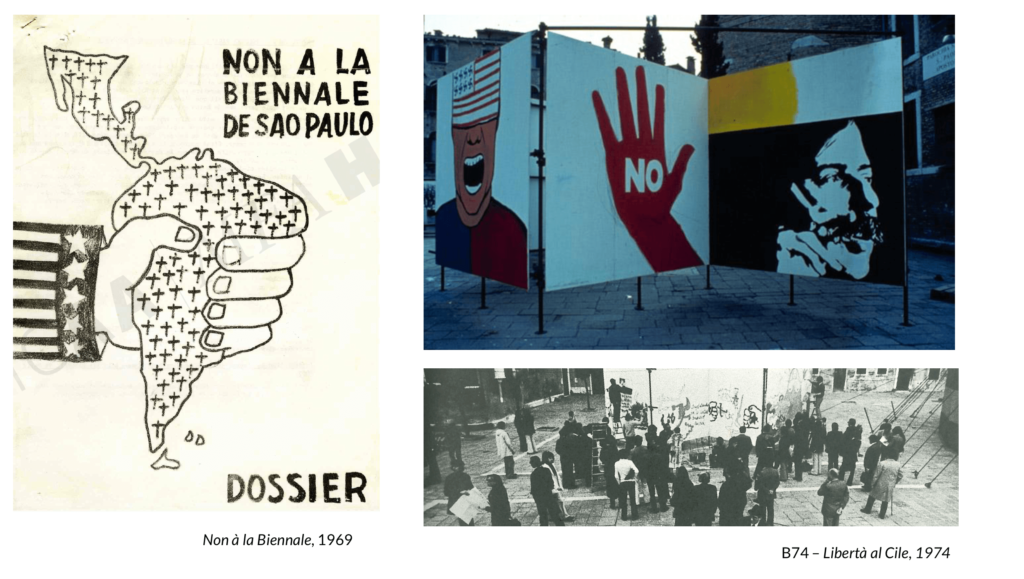

The following intervention, entitled “Rethinking the counter biennials: agents of resistance with potential to enact lasting changes in the biennial system?”, was also focused on transnational exhibitions. Anita Orzes analysed the polemics that have shaken the São Paulo Biennial and the Venice Biennial between the 1960s and 1970s, wondering, on the one hand, if it is possible to talk about “biennials of resistance” and, on the other hand, how these biennials have been a vehicle for the creation of transnational communities and new counter-geographies. Starting with the boycott of the 10th São Paulo Biennial (Non à la Biennale), and contextualizing it within the military dictatorship in Brazil and the censorship that had taken place at the 2nd Bahia Biennial or the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art of Rio de Janeiro, she delineated transnational networks that connected Brazil, France, Italy and the United States. The boycott Non à la Biennale was followed by the Contrabienal (1971), a counter-biennial in book format that, on the one hand, rejected a biennial organized by a government as synonymous with a system of repression and brutal torture and, on the other hand, rejected what this event represented, that is, an instrument of cultural colonization in the countries of Latin America. In fact, many biennials at that time were going through a phases of contestation and reformulation of their format. Both Venice and São Paulo have played a prominent role in these discussions. B74 – Libertà al Cile (Venice Biennial, 1974) is a good example for both, the new biennial format and the transnational solidarity developed through exhibitions. The biennial became a cultural action against the Pinochet regime. It was intended to inform and sensitize the public of the Biennial and the Italian public opinion. In addition, the biennial was “decentralized”, spreading throughout Venice and also in the extra-urban and working-class areas of Mestre and Marghera. Anita Orzes offered an analysis of the exhibitions (e.g. the exhibition of Chilean posters made between 1970 and 1974, the photo exhibition Immagini e parole dal Cile: da Allende alla Repressione and the murals of the Salvador Allende Brigade) as well as the meetings (e.g. Italia – Cile: lavoro, politica e cultura), comparing this edition of Venice Biennial with another artistic initiative of solidarity in Italy (Mostra incessante per il Cile[2], 1973-1977) and with the Italian political reality of the 1970s (the “new” resistance). Finally, she wondered whether the legacy of these biennials is still alive or whether they have been relegated to a footnote, pointing out that an initial answer could be found in All the World’s Future (56th Venice Biennial) curated by Okwui Enwezor.

The following paper “The Island of negative Utopia. New York’s late seventies: art and resistance at a crossroads” by Olga Fernández López focused on the United States and on creation of the category of “underclass”[3] and the defence of deprived neighbourhoods in the 1980s. She structured her intervention in three interrelated parts: the analysis of transnational (dis)encounters, the representation of victims and the community art. The so-call “underclass” defended their neighbourhoods, grown from various migration/diaspora- waves, with a cosmopolitan attitude. They conformed ghettos/islands that established a kind of “internal transnationality”, pivoting between the US and their countries of origins. Artists used social art as an umbrella for their political activities. One of the consequences was that they didn’t produce objects or images but community(ies), both of people and artists. An example was Joseph Beuys, invited to the US several times and a reference figure for the New York artists of the 1980s. Beuys believed in the social value of art and considered it as an agent for social change: the creative development of all people, promoted through the arts, would generate the initiative necessary for revolution. Other artists like Willoughby Sharp and Liza Béar had a similar desire to use art as a revolutionary tool in society. Some examples are the two shows “The Real Estate show” (1979) and “Times Square Show” (1980), organized by Collaborative Projects Inc., which lead to the foundation of ABC no Rio. The political themes of the collective were American wealth, class and power, recessions of 1970s, housing crisis, homelessness and gentrification. Finally, moving from the seventies to the eighties, Olga Fernández López explained the shift of Lucy Lippard between these two decades and after her trips to the UK, China, Cuba and Nicaragua. A significant event was the exhibition Art from the British Left (1979), announced as the first in a series of presentations of “socially concerned art”. It led to the PAD/D‘s (Political Art Documentation/Distribution) conception (1981) that brought together politically committed artists from veteran groups (Art Workers Coalition and Fluxus) and from younger organizations (Heresies collective and Group Material). They used spaces and collaborated with other organizations for their political actions, such as Out of Place: Art For the Evicted (El Bohio, 1983) and Art for the Evicted: A Project Against Displacement (El Bohio, 1984). Here they plastered the facades of abandoned buildings at Losaida with artworks in order to call attention to the gentrification. To conclude, she emphasized the “political art as a contact zone” that can be analysed through some exhibitions (e.g. The Nicaragua Media Project) and performances (e.g. The True Avenue of the Americas) of the Artists Call Against the US intervention in Central America.

The last paper of the afternoon was “Femmes dans les collectifs de cinéma ou le genre à l’épreuve de la praxis (Amérique latine, 1970-1989)”. Sonia Kerfa explained her aim to rethink the place and role of women in political and revolutionary film production through the study of various women collectives, for example Cine mujer México (1975), Cine mujer Colombia (1978) and Grupo Miércoles (1978). She proposed a redefinition of the accepted revolutionary means of films through a gender perspective. The themes addressed in these films (rape, menstruation or male violence) underline the choice of making a cinema based on experience, on real-life stories and on the female body, but also on social protest movements and on social memory. This feminist approach deconstructs existing images in order to de-anesthetize the canonical images of women. During her presentation, the importance of highlighting the places where these films were shown and the audience to which they were addressed was also stressed, as well as the interest of reflecting on the names of the groups, since accompanying the word “cinema” with the word “woman” is not a neutral gesture.

The workshop Partisan genealogies: counter-visualities from the WWII allowed to debate a broad imagery connected to the partisan struggle, the notion of the partisan itself, assessing the heterogeneity of its status, the multiple ways and manners of claiming rights and the places of partisanship. Finally, we discussed the role of multiple exhibitions that, with a partisan character, help to build solidarity networks and created counter-geographies that connected the Western World, the Socialist bloc, the Third World and the Non-aligned countries.

[1] Rosendo Soto was an artist of the “second” generation of muralists. He and the artist Ignacio Marquez Rodiles were the people in charge of travelling with the exhibition in Europe for 10 months. They also organized talks, round tables, press releases and conferences.

[2] Catenacci, Sara: “Solidarity and socially engaged art in 1970s Italy” in Khouri, Kristine; Salti, Rasha (eds.), Past Disquiet: Artists, International Solidarity and Museum in Exile, Warsaw, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2019, pp. 259-277. The Mostra incessante per il Cile was conceived as a non-stop exhibition starting in 1973. The activities were organized both into the Milanese Gallery of Porta Ticinese (Milan) and outside the gallery space, in collaboration with workers, students or socially engaged groups. The end of the Mostra incessante per il Cile corresponded with an exhibition to document the experience in 1977.

[3] The term “underclass” refers to poor people, mainly black, whose behaviour is considered criminal, deviant or simply different from that of the middle class. See Welshman, John, Underclass: A History of the Excluded since 1880, London, Bloomsbury Academic, 2013.